Professional learning is a critical part of developing effective educators and school leaders. In Texas, classroom teachers, administrators, and counselors who work with gifted students need initial and annual follow-up training (i.e., 6-hour updates). Educators are busier than ever before, but case studies are one flexible professional learning tool that can be used to examine issues faced by students with advanced learning needs, their caregivers, and professionals in the schools (see also Boswell & Weber, 2022; Weber et al., 2016). Professional learning can help educators support equity and excellence in their classrooms by embracing strengths-based, asset-focused approaches to identify and serve students from culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse backgrounds (Ford & Grantham, 2003; Plucker & Peters, 2016). Case studies can provide a framework to examine strengths and areas for improvement through open discussions about school policy and instructional strategies.

In education, the focus is often on ensuring that all students can meet grade-level standards in core academic subjects. Not only can students with advanced learning needs be overlooked in this type of accountability system, but also the system itself can create a culture of deficit thinking in which educators and school leaders spend their energy filling gaps and not on spotting potential or providing advanced learning opportunities (Dixson et al., 2020; Plucker & Callahan, 2020). However, strengths-based, asset-focused strategies, such as frontloading, flexible ability grouping, and psychosocial interventions have strong research support and can transform learning environments into places where every student can learn something new every day (Meyer et al., 2023; Plucker & Peters, 2016). The cases in this collection explore a variety of scenarios related to students with advanced learning needs.

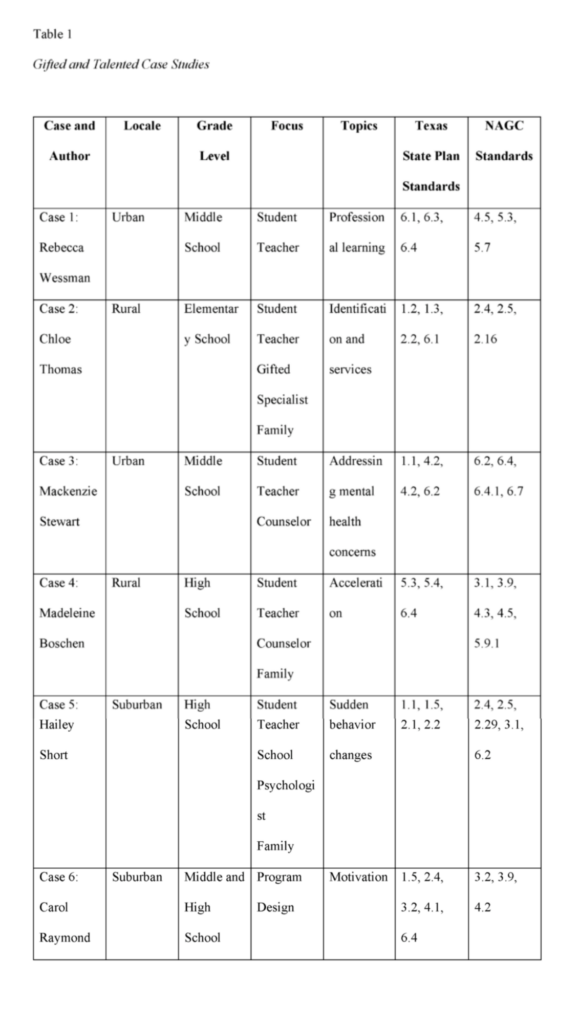

These six case studies can be a catalyst for independent reflection and to start critical conversations among colleagues about identifying and serving students with advanced learning needs. Each case includes (a) a scenario, (b) discussion questions, (c) notes, (d) topics for conversation, (3) National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC, 2019) Pre-K–Grade 12 Gifted Education Programming Standards, (f) standards from the Texas State Plan for the Education of Gifted/Talented Students (Texas Education Agency [TEA], 2019), and (g) TEMPO+ resources for additional reading. These cases can be used in large-group, small-group (e.g., professional learning communities), or self-directed learning contexts. The hypothetical scenarios present a range of school settings and topics (see Table 1), so educators can choose cases relevant to their job roles or work through all of the cases to gain a broader perspective. These studies can also serve as models for educators who want to create scenarios tailored to their unique contexts. The possibilities are endless.

Each case study provides an opportunity to dive deeply into the challenges of identifying and serving students with advanced learning needs. You can also check out the companion collection of case studies about twice-exceptionality on TEMPO+. We hope this collection of cases leads to meaningful conversations and asset-based action plans.

TEMPO+ Resources for Additional Reading

Additional Open Access Case Studies

Meyer, M. S., & Guilbault, K. M. (2022). Case profiles in gifted education and talent development.

Case Study 1: Professional Learning for Educators Who Work With Gifted Students

Rebecca M. Wessman

Liberty Middle School

Mrs. Lopez is returning to teaching after a 5-year retirement. Prior to retirement, she taught sixth-grade math and offered tutoring outside of school. She taught for 11 years before retiring due to burnout. Mrs. Lopez graduated with an undergraduate degree in education, and since her retirement, she has spent much of her time traveling, attempting a startup business, and lying on the beach. She has grown bored without teaching and has decided to accept a position in a large urban public school. Liberty Middle School serves students in sixth to eighth grade and has 950 students enrolled. Mrs. Lopez is passionate about math and is thrilled to accept a new position as a seventh-grade math teacher. She is excited to be teaching an accelerated math course that combines eighth-grade math and Pre-Algebra. Each of her three classes has about 20 students.

Mrs. Lopez spent the summer working hard to prepare her classroom and the content for each of her classes. She communicated with the other teachers in her department to discuss how the content has been taught in the past. She has also completed district onboarding and attended training for Liberty Middle School. Because she has been retired for 5 years, Mrs. Lopez is concerned that she may have forgotten some skills, but she is confident that she is well prepared for the new school year. After all, she has 11 years of experience.

After welcoming her students and getting to know them in the first few weeks of the school year, she begins to notice certain characteristics about individual students. A large group of her students are just as passionate about math as she is, and oftentimes, they fly through their classwork before some students can even begin. Mrs. Lopez makes note of one student in particular, Aisha.

Aisha

Aisha is a 12-year-old girl who has been at Liberty since she started middle school. She is on the track team and volunteers weekly at the Boys and Girls Club to show her love for the community. Aisha is the oldest in her family and holds herself to a very high standard. She maintains excellent grades and does exceptionally well in math. Aisha is in the top math class for her grade, but she consistently finishes her work well before the other students. When she does complete work early, she occasionally assists her peers, reads, or completes extra practice problems. Before this year, her math teachers differentiated lessons to address her advanced learning needs and made sure that her extra time in class was setting her up for success in future advanced math courses. However, Mrs. Lopez has not done anything to differentiate for Aisha. She is aware that Aisha has been identified for gifted services, including this seventh-grade compacted math class, but she is unsure what she can do for Aisha outside the curriculum. Because Aisha has not spoken up about wanting content that is more challenging and Mrs. Lopez doesn’t want to load her down with extra work, she has settled for allowing Aisha to finish early and work on other school assignments.

Although Aisha’s grades have stayed strong, Mrs. Lopez notices that she is not as motivated as she was at the beginning of the year and does not engage in the lessons or with her peers. Mrs. Lopez thinks this could be due to normal teen tendencies, so she notifies Aisha’s parents and encourages them to practice at home with her. Aisha’s other teachers are not seeing these issues, but they share ways they have differentiated their content for Aisha. Mrs. Lopez is hopeful she can turn this situation around, but she’s unsure of how to differentiate an already accelerated course. Her mentor teacher suggests that she look at some online resources on differentiation and acceleration. Mrs. Lopez is realizing that her most recent training did not prepare her for this situation. Aisha’s issues with motivation and engagement are confined to math only, and her parents do not see these tendencies when they practice at home with her. Mrs. Lopez has begun her quest for online resources and training so she can begin to push Aisha toward the next level. She has also started asking around campus for training that could help her better serve her students with advanced learning needs.

Discussion Questions

- What are some common ways teachers handle students who master content quickly and finish assignments early? Are these practices effective for students with advanced learning needs?

- Where might Mrs. Lopez find training or resources to learn best practices for differentiating for the needs of gifted and talented students?

- What can teachers of accelerated courses like the one Mrs. Lopez teaches do to monitor the growth of learners with needs beyond the course content?

- What resources have helped you learn to meet different student learning needs (e. g., conferences, training, book studies)?

Case Study Notes

Focus: A seventh-grade math teacher in an urban school needs support to differentiate for a student with advanced math abilities.

Key points:

- Mrs. Lopez is returning to the classroom after 5 years away.

- She has 11 years of experience as a math teacher.

- Aisha has been identified for gifted services and is involved in many extracurricular activities, such as sports and volunteering.

- Mrs. Lopez has learners who finish their accelerated math work early, so she lets them help others, read, or work on assignments for other classes.

- After being out of the classroom for a while, Mrs. Lopez is unsure how to best serve her students with advanced learning needs.

Potential discussion topics:

- Professional learning on differentiating instruction

- Resources and accommodations that might help students who master course content quickly

- School- or district-based professional learning

- Other resources for professional learning on advanced learning strategies

NAGC Standards

- 6.1. Talent Development. Students identify and fully develop their talents and gifts as a result of interacting with educators who possess content pedagogical knowledge and meet national teacher preparation standards in gifted education and the Standards for Professional Learning.

- 6.3. Equity and Inclusion. All students with gifts and talents are able to develop their abilities as a result of educators who are committed to removing barriers to access and creating inclusive gifted education communities.

- 6.4. Lifelong Learning. Students develop their gifts and talents as a result of educators who are lifelong learners, participating in ongoing professional learning and continuing education opportunities.

Texas State Plan Standards

- Curriculum and Instruction: Districts meet the needs of gifted/talented students by modifying the depth, complexity, and pacing of the curriculum and instruction ordinarily provided by the school.

- 4.5 Opportunities are provided to accelerate in areas of student strengths (19 TAC §89.3(4)).

- Professional Learning: All personnel involved in the planning, creation, delivery and administration of services to gifted/talented students possess the knowledge required to develop and provide differentiated programs and services.

- 5.3 Teachers are encouraged to obtain additional professional learning in their teaching discipline and/or in gifted/talented education.

- 5.7 Annually, each teacher new to the district receives an orientation to the district’s gifted/ talented identification processes and the district’s services for gifted/talented students.

TEMPO+ Resources for Additional Reading

Case Study 2: Explaining Gifted Identification and Services to Parents

Chloe M. Thomas

Heritage Public School

Heritage Public School is a K–12 school located in rural Texas that has an enrollment of 893 students. As the only school in the town, Heritage receives overwhelming support from the community. Parents are very involved with their children’s education and the community rallies around school activities. Mrs. Jefferson has worked at Heritage for 27 years, with 8 years in kindergarten and 19 years as the gifted and talented specialist for K–12. Many years ago, Mrs. Jefferson saw a void in the gifted education services at her school. Students weren’t being referred and therefore not tested or provided advanced learning services. In addition, teachers weren’t given relevant resources to help students in their classes who needed additional learning challenges. She talked with her district about creating a new position. The educator in this role could conduct testing, provide services, and communicate with parents about student potential. After a few years, Mrs. Jefferson completed her master’s in gifted education, earned her state certification for gifted and talented, and became the school’s gifted and talented coordinator working directly with students and their families.

Once a month she spends 45 minutes with each kindergarten and first-grade class conducting enrichment activities. She spends that time using read-alouds, media, and small projects to teach grade-level concepts to the class. While working with the students, she is also gathering data to identify students with advanced learning needs and providing teachers with hands-on differentiation training and talent-spotting activities they can use. All students are universally screened in the second grade using the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT) to assess their reasoning skills with verbal, quantitative, and nonverbal questions. In the event that a student is not assessed or identified for gifted services in second grade, a referral from the classroom teacher or Mrs. Jefferson is needed for testing in later grades. The school uses local norms due to the diverse population of students and the research evidence supporting this practice. After testing, parents are notified of the results and how their student’s education services will change. Mrs. Jefferson meets with elementary and middle school students identified for gifted services by grade level once a week in a pull-out class. She also works with the school counselor, Mr. Yang, to help with advanced course offerings (e.g., Advanced Placement [AP], dual-credit) and college and career readiness interventions for her gifted students in high school.

The Castillo Family

The Castillo family recently moved from Atlanta and their daughter, Jessica, has been zoned to Heritage. Jessica went to a small urban private school where she received impressive reports from former teachers. Aside from her high grades, her former teachers made no note of advanced learning needs or identification for gifted services. Over time, Jessica began to fall behind in her new class. She stopped trying to engage with her classmates and began acting out. The counselor and principal have now had multiple meetings with her parents to discuss her behavior. They believe the adjustment to a new school is taking its toll and she is just lashing out in response to her new circumstances.

In an effort to help Jessica, the counselor met with her to discuss her life changes. Jessica described her classes as boring and said she feels like she’s already learned everything her new teachers are presenting. She doesn’t understand why she has to be in a class where nothing they ever do is challenging. Based on this conversation, the counselor pulled in Mrs. Jefferson to explore the possibility of evaluating Jessica for gifted services, providing her with differentiation in her current classes, and offering acceleration in courses where she can demonstrate mastery.

Mrs. Jefferson observed Jessica in class and saw her lack of focus during whole-group instruction, but when she interacted one-on-one with Jessica, she saw that her understanding of the topic was well beyond what had just been taught. Jessica also began chatting excitedly to Mrs. Jefferson about books she was reading and her extracurricular interests. Based on her observations of Jessica, Mrs. Jefferson decided to move forward with testing for gifted services. Mrs. Jefferson called Jessica’s parents and explained that she wanted to assess her so she could receive pull-out instruction. Mr. and Mrs. Castillo are unfamiliar with gifted and talented services and can’t see how that will help Jessica’s behavior. They are also worried about her missing class time for pull-out instruction. They want her to remain in class and do better at following class procedures and engaging with her peers. Her parents do not believe she needs a gifted label. Mrs. Jefferson can’t move forward with assessment and identification without the parents’ consent, so she suggests having an in-person meeting to go over the implications and benefits of gifted identification and service.

Discussion Questions

- What are some possible reasons Jessica went unidentified in her old school?

- How can Mrs. Jefferson address the concerns of Mr. and Mrs. Castillo?

- What benefits should Mrs. Jefferson explain to show the full scope of gifted education at Heritage?

- In the event that her parents do not agree to evaluation for gifted and talented services, what could be done in the classroom to support Jessica’s advanced learning needs?

Case Study Notes

Focus: A gifted and talented specialist in a rural school works with a student whose parents aren’t sure how gifted services will benefit their daughter.

Key points:

- Jessica was previously an enthusiastic and engaged student.

- After moving to Heritage, Jessica began refusing to complete classwork and began to isolate herself socially.

- Mrs. Jefferson believes that a lack of support for Jessica’s advanced learning needs may be the cause of her academic and behavioral issues.

- Mr. and Mrs. Castillo are not familiar with gifted education identification or programming and don’t believe it will help Jessica.

- Mrs. Jefferson wants to explain how advanced learning services might help Jessica.

Potential discussion topics:

- Indicators that a student might have advanced learning needs

- Ways to gain parental support for evaluation and testing

- Creating collaborative home-school partnerships

NAGC Standards

- 1.2. Self-Understanding. Students with gifts and talents demonstrate understanding of how they learn and recognize the influences of their identities, cultures, beliefs, traditions, and values on their learning and behavior.

- 1.3. Self-Understanding. Students with gifts and talents demonstrate understanding of and respect for similarities and differences between themselves and their cognitive and chronological peer groups and others in the general population.

- 2.2. Identification. Students with gifts and talents are identified for services that match their interests, strengths, and needs.

- 6.1. Talent Development. Students identify and fully develop their talents and gifts as a result of interacting with educators who possess content pedagogical knowledge and meet national teacher preparation standards in gifted education and the Standards for Professional Learning.

Texas State Plan Standards

- Student Assessment: Gifted/talented identification procedures and progress monitoring allow students to demonstrate and develop their diverse talents and abilities.

- 2.4 Families and staff are informed of individual student assessment results and placement decisions as well as given opportunities to schedule conferences to discuss assessment data.

- 2.5 An awareness session providing an overview of the assessment procedures and services for gifted/talented students is offered for families by the district and/or campus prior to the referral period.

- 2.16 Students in grades K–12 shall be assessed and, if identified, provided gifted/talented services (TEC §29.122 and 19 TAC §89.1(3)).

TEMPO+ Resources for Additional Reading

Rambo-Hernandez, K. (2020, August). Local norms, nuts, bolts, and benefits. TEMPO+.

Case Study 3: What’s Weird When It’s All Weird? Addressing Mental Health Concerns

Mackenzie Stewart

Ms. Hart and Sally

Ms. Hart teaches in a large, urban, middle school that serves a diverse student population. In this school district, students who receive gifted and talented services are identified due to outstanding levels of aptitude in core content subjects, such as math or language arts. Students identified for gifted services can take advanced courses in many subjects and Ms. Hart teaches both advanced and grade-level math to a total of 70 students a day. In one of the advanced seventh-grade math classes, there are 10 students who Ms. Hart sees once a day. Over the course of the last 2 weeks, there is one student whose behavior has been noticeably different from usual; however, it is middle school, and in middle school, a lot of students have behavior changes as they grow and figure out who they are and who they want to be.

Sally and her three friends usually sit together in class, but recently she has been sitting apart from the others. Although Sally was always a quiet and reserved student, she has started to put her head on the table during class and has not turned in her homework for the last couple of weeks. On the most recent in-class quiz, she got more than half of the questions wrong, even though she is typically a straight-A student. Math has always been easy for Sally, and she has never had to study before. Thus, as the middle school math class becomes more difficult, Sally has struggled to keep up. This is something that happens every year as students with advanced learning needs transition from elementary to middle school, so Sally’s teacher is not sure if she should do or say something.

Sally’s other two friends have been disruptive in class, so Ms. Hart wonders if this could be the reason Sally has started to distance herself. Her friends talk loudly and laugh at other students when they answer a question wrong. When they laugh at Sally, Ms. Hart hears her remark, “Who cares about any of this anyway?” This surprises her teacher, so she decides to talk to some of the other middle school teachers to better understand the situation.

First, Ms. Hart heads down to the homeroom that all three girls share. Ms. Smith, the homeroom teacher, mentions she has not noticed anything unusual for these middle school students. She reminds the math teacher that these girls spend almost their whole day together in advanced subjects and that can cause some added tension and stress. When Ms. Hart asks her if Sally seems quieter, she does note that Sally did not want to participate in any of the fun holiday activities that she put out every morning. But she also makes it clear that a lot of middle school students think they are too cool for these types of activities. Not feeling satisfied with this answer, Ms. Hart decides to meet with a few other teachers. Many of them have noticed similar events, but none of them are as concerned as she is. They remind her that middle school girls fight and make up all of the time.

Mr. Gonzales

In the end, Ms. Hart decides that these behavior changes are too concerning to ignore, so she follows the protocol for a suspected mental health crisis and reports Sally’s behavior to the school counselor. In the report, Ms. Hart mentions Sally’s loss of interest in class, grade changes, and lack of energy and motivation. She also documents the out-of-character comment that Sally made during the last class. The school counselor, Mr. Gonzales, promises to look into the situation. He brings each girl down to his office separately, talks to them, and explains why teachers have expressed concern about their behavior. He wants his office to be a safe space, so he reminds each student that what they share is confidential, provided they have no plans to harm themselves or others. Mr. Gonzales has no pressing concerns about the other two girls and talks with them about being more respectful to their teachers and classmates, but he believes Sally is experiencing depression. Sally agrees to bring her parents in to talk about how she is feeling and after meeting with the school counselor, they contact a therapist who has experience with adolescents and make an appointment for Sally.

Mr. Gonzales meets to follow up with Ms. Hart. He thanks her for bringing the situation to his attention and commends her for not ignoring the warning signs or writing off the changes she saw in Sally as typical middle school behaviors. Ms. Hart understands now that changes in behavior lasting 2 weeks or longer can indicate depression, anxiety, or worse. Mr. Gonzales gives Ms. Hart some resources to learn more about adolescent mental health and how to intervene if she senses another student might be in crisis.

Discussion Questions

- What warning signs of mental health issues may overlap with typical adolescent behavior?

- What is the biggest indicator that behavioral issues may need professional intervention?

- What can education professionals do to address mental health issues in classroom contexts?

- What conversations related to mental health are appropriate for classroom teachers to have with students?

- Which types of conversations should be referred to mental health professionals?

Case Study Notes

Focus: A teacher works with other school personnel to support a gifted middle school student who is experiencing mental health issues.

Key points:

- Sally has been quieter than usual and stopped turning in homework.

- She has made comments within earshot of friends and teachers that are concerning.

- It can be difficult to distinguish between typical middle school behavior and something more serious.

Potential discussion topics:

- Student behaviors that could indicate mental health issues

- Symptoms of depression in adolescents

- Age-appropriate ways to discuss mental health with students

- School protocols for reporting a suspected mental health crisis

- School resources to assist classroom teachers in supporting student mental health

NAGC Standards

- 1.1. Self-Understanding. Students with gifts and talents recognize their interests, strengths, and needs in cognitive, creative, social, emotional, and psychological areas.

- 4.1. Personal Competence. Students with gifts and talents demonstrate growth in personal competence and dispositions for exceptional academic and creative productivity. These include self-awareness, self-advocacy, self-efficacy, confidence, motivation, resilience, independence, curiosity, and risk-taking.

- 4.2. Social Competence. Students with gifts and talents develop social competence manifested in positive peer relationships and social interactions.

- 6.2. Psychosocial and Social-Emotional Development. Students with gifts and talents develop critical psychosocial skills and show social-emotional growth as a result of educators and counselors who have participated in professional learning aligned with national standards in gifted education and Standards for Professional Learning.

Texas State Plan Standards

- Family/Community Involvement: The district involves family and community members in services designed for gifted/talented students throughout the school year.

- 6.2 Input from family and community representatives on gifted/talented identification and assessment procedures is invited annually.

- 6.4 The opportunity to participate in a parent association and/or gifted/talented advocacy groups is provided to parents and community members.

- 6.4.1 Support and assistance is provided to the district in gifted/talented service planning and improvement by a parent/community advisory committee.

- 6.7 Orientation and periodic updates are provided for parents of students who are identified as gifted/talented and provided gifted/talented services.

TEMPO+ Resources for Additional Reading

Lewis, K. D., Miller, J. E. K., Kabli, A., Majority, K. L., Roberson, J. J., Brown, B., & Desmet, O. A. (2020, December). What the research says: Motivation for achievement and causes of underachievement. TEMPO+. https://tempo.txgifted.org/what-the-research-says-motivation-for-achievement-and-causes-of-underachievement

Majority, K. L., Lewis, K. D., Dearman, C. T., Troxclair, D. A., Miller, J. E. K., & Kabli, A. (2019, August). What the research says: Social-emotional issues in gifted education. TEMPO+. https://tempo.txgifted.org/what-the-research-says-social-emotional-issues-in-gifted-education

Case Study 4: Supporting Single-Subject Acceleration for High School Students With Advanced Learning Needs

Madeleine G. Boschen

Jana

Jana is a 17-year-old student in a rural Texas school district. She is one of 216 students attending her high school. Jana has continuously received high grades because she believes it is important to do well in school and she wants to make her family proud. Her teachers note that she is exceptionally bright. In fact, her first-grade teacher recommended accelerating her to the second grade, but her parents declined in favor of keeping her with same-age peers because they worried about the potential social issues Jana might face. Jana was later formally identified for gifted and talented services during second grade and has continued to receive those services into middle and high school. Jana scored 1490 on the PSAT in her sophomore year of high school and 1520 out of 1600 on her most recent SAT. However, Jana has expressed a desire to retake the SAT because she thinks she can improve her score now that she knows the format and timing of the test. She maintains close relationships with many of her former teachers but has always favored her science teachers. Mrs. Rodriguez, the science teacher at the high school, is her favorite.

Jana has demonstrated an interest in science since a first-grade unit on the properties of matter and dedicates much of her free time to various scientific subjects and investigations through free online resources and websites. She is deeply inquisitive and fiercely loyal to her family and community. Despite her love of learning, she has always placed her family and friends first. When she received a telescope for Christmas one year, she made sure everyone in the family tried it out before she was willing to take a turn. Over the years, her parents have become more supportive of her passion for science and pride themselves on their daughter’s achievements. They make sure to show guests her first-place trophy from the regional science fair whenever they visit their home. Despite not fully understanding Jana’s interests, they do their best to support her.

After her junior year, Jana will have officially exhausted the science course offerings at her school. She has completed every AP (biology, chemistry, and physics) and honors (earth science and environmental science) science course offered, so in her senior year, she will have no more science classes to take. This has become a source of disappointment for Jana, and teachers, family, and friends have all noticed a difference in her normally lively personality. In addition, Jana has expressed concerns about graduating because she is unsure of the path she wants to take following high school. She feels conflicted about whether she should attend college to pursue further education and a STEM career or remain close to her community and friends. She recently shared these anxieties with her mother. Jana’s increasingly despondent attitude has begun to concern her parents, leading them to reach out to her science teacher, Mrs. Rodriguez, to ask her to keep an eye on Jana. During their short call with Mrs. Rodriguez, Jana’s parents mentioned her distress at the thought of leaving her family and hometown in order to attend college, as well as her dreams of pursuing a career in science. Following this communication, Mrs. Rodriguez scheduled a meeting for Jana and her parents to discuss these issues with the high school counselor, Mrs. Faye.

Mrs. Faye’s Dilemma

Mrs. Faye often feels overwhelmed with her work as the sole counselor at the high school. She is responsible for scheduling, academic advising, and the well-being of the students. She has a true desire to help every one of her students, but she only has so much time. Mrs. Faye is somewhat familiar with Jana and her situation. She helped adjust her schedule freshman year to include an additional science course and knows that Jana has been identified for gifted and talented services. Following a discussion with Mrs. Rodriguez about Jana’s changes in demeanor, she was happy to meet with Jana and her parents to discuss college plans, her courses for next year, and her overall mental and emotional well-being. Mrs. Faye is familiar with strategies for guiding students through the transition from high school to college, but she wishes she had more information about students with advanced learning needs. She has not been able to attend any conferences or professional learning sessions focused on gifted education at the state or national level in her few years as a counselor. She is not sure what specific recommendations to make for Jana. She thinks Jana has strong potential to excel in college but wants to come to a solution that is agreeable to everyone. She has written an agenda for the meeting with Jana and her parents:

- Ask Mrs. Rodriguez about community mentors. Contact the water treatment center?

- College Prep Night is the third week of May. Date TBD

- Community college courses. Need to research science courses. Maybe evening?

- Ask about SAT scores

- Find out major/career interests

- Take a look at schools of interest. State? Private?

- Available AP math courses for senior year: AP Calculus, AP Statistics

- Ways to alleviate stress/negative emotions. Follow-up meeting? Referral?

Mrs. Faye thinks this agenda will help guide the conversation and identify several ways to help Jana and her family as they make decisions about her future after high school.

Discussion Questions

- Mrs. Faye is unfamiliar with options for high students who have moved through courses at an accelerated rate. What could she suggest as a path forward for Jana’s senior year?

- Jana’s senior year courses currently include no science, an area in which she excels. Based on the Texas State Plan, what potential solutions can Mrs. Faye can investigate, coordinate, or offer?

- Jana and her family are anxious about her transition from high school to life post-graduation. What resources can Mrs. Faye offer? What strategies could she implement to support Jana?

Case Study Notes

Focus: A school counselor works with an accelerated student as she transitions into the final year of high school.

Key points:

- Jana has a relatively strong support system at school and home.

- Jana has very strong ties to her family and her rural community which she may prioritize when weighing potential solutions.

- Jana has advanced academic needs in science, and she regularly explores these areas of interest virtually in her free time.

- Jana’s overall demeanor has changed.

Potential discussion topics:

- School context

- Remote learning

- High school to college transitions

- High school to career transitions

- College and career readiness

- Counseling/postsecondary advising for students with advanced academic needs

NAGC Standards

- 5.3. Career Pathways. Students with gifts and talents create future career-oriented goals and identify talent development pathways to reach those goals.

- 5.4. Collaboration. Students with gifts and talents are able to continuously advance their talent development and achieve their learning goals through regular collaboration among families, community members, advocates, and the school.

- 6.4. Lifelong Learning. Students develop their gifts and talents as a result of educators who are lifelong learners, participating in ongoing professional learning and continuing education opportunities.

Texas State Plan Standards

- Service Design: A flexible system of viable service options provides a research-based learning continuum that is developed and consistently implemented throughout the district to meet the needs and reinforce the strengths and interests of gifted/talented students.

- 3.1 Identified gifted/talented students are assured an array of learning opportunities that are commensurate with their abilities and that emphasize content in the four (4) foundation curricular areas. Services are available during the school day as well as the entire school year. Parents are informed of these options (19 TAC §89.3(3)).

- 3.9 Local board policies are developed that enable students to participate in dual/concurrent enrollment, distance learning opportunities, and accelerated summer programs if available.

- Curriculum and Instruction: Districts meet the needs of gifted/talented students by modifying the depth, complexity, and pacing of the curriculum and instruction ordinarily provided by the school.

- 4.3 A continuum of learning experiences is provided that leads to the development of advanced-level products and/or performances such as those provided through the Texas Performance Standards Project (TPSP) (19 TAC §89.3(2)).

- 4.5 Opportunities are provided to accelerate in areas of student strengths (19 TAC §89.3(4)).

- Professional Learning: All personnel involved in the planning, creation, delivery and administration of services to gifted/talented students possess the knowledge required to develop and provide differentiated programs and services.

- 5.9.1 Counselors who work with gifted/ talented students receive a minimum of six (6) hours annually of professional development in gifted/ talented education.

TEMPO+ Resources for Additional Reading

Case Study 5: Supporting the Social, Emotional, and Psychosocial Health of High-Achieving Secondary Students

Hailey Short

Martha

Martha is a 16-year-old junior at a mid-sized, suburban high school with 1,500 students. Throughout her academic career, Martha has excelled. This year, she is enrolled in both honors and AP courses. Martha is highly involved on campus; she is a member of her school’s drama program and plays on the varsity volleyball team. Martha has a good relationship with her parents and is especially close to her younger sister, Charlotte, a freshman at the same high school. Martha’s two best friends, Christian and Lauren, are also involved in the drama club.

Martha has always been a motivated student. She begins working on her homework as soon as she gets home from school. Still, she also has a few bad habits. She is chronically late, her locker and bedroom are always a mess, and she can be quite forgetful. She always jokes that there are too many tabs open in her brain. At the beginning of the school year, on top of all her other activities, her mother suggested she enroll in an SAT preparation course. Lately, however, Martha has been struggling to stay motivated. Most days, she takes long naps when she returns home from school and has forgotten about several homework assignments.

In the fall, Martha’s volleyball coach began noticing concerning behaviors. When given corrections, Martha’s reactions were highly emotional. She cried often, got upset easily, and snapped at her coach. Each time, she was immediately apologetic, but it was affecting her relationship with her coach and teammates. When the coach approached Martha’s parents about her behavior, her father insisted she was just going through a rough patch. Martha’s teachers have also been noticing changes in her behavior. She has made careless mistakes on assignments and often seems to be in a world of her own. When Lauren asked if she was going to audition for the spring musical, Martha said she didn’t feel like it. This was surprising because, until now, Martha had never missed an audition. Her family and friends always said she was most herself when she was on the stage, and she seems to love theater more than anything.

Lauren expressed her concerns to Charlotte, who agreed that Martha had not been acting like herself lately. Lauren, Charlotte, and Martha’s mother decided to encourage Martha to talk to the school counselor, Ms. Cullen, about how she had been feeling. Martha agreed. After opening up about her personal and academic struggles, Ms. Cullen suggested Martha speak to Mr. Banks, the school psychologist. Mr. Banks agreed that the shift in Martha’s academic performance and social involvement was cause for concern, so he started a comprehensive assessment. When Mr. Banks completed the cognitive assessment for Martha, her scores were consistent with her previous levels of academic performance. Despite her current academic struggles, Martha’s teachers and other school administrators did not believe she needed additional services. The school argued that AP and honors classes are the services recommended for advanced learning needs, so there was nothing more they could do for Martha.

However, Mr. Banks suspected that cognitive supports were not what Martha truly needed to succeed, so he continued to look further into Martha’s case. Mr. Banks conducted observations of Martha in class, at lunch, and at volleyball practice to determine if her symptoms were occurring across multiple settings. Finally, Mr. Banks conducted interviews with Martha, her parents, her coaches, and her teachers to understand how her performance in the classroom had changed in the last few months. Martha’s volleyball coach noted that she had been a daydreamer since he first met her 4 years ago. Her parents reinforced that some of Martha’s symptoms were present earlier, noting that because of the mess in her room and now her car, they have called her “Hurricane Martha” since she was 8 years old.

Mr. Banks suspected Martha may have Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), so he suggested she speak to her primary care provider, Dr. Brown. During her appointment, Dr. Brown diagnosed Martha with ADHD, inattentive type. Following Martha’s appointment, Dr. Brown, Mr. Banks, and members of her school’s multidisciplinary team collaborated in the development of a 504 Plan. Dr. Brown completed a form indicating Martha was eligible for 504 services under other health impairment (OHI). Mr. Banks invited Martha’s parents and teachers to attend her first 504 meeting. Cognitively, Martha is already receiving the best services—AP and honors classes. However, Mr. Banks recommended interventions to support Martha’s ADHD.

Now, her teachers have placed her desk in the front of the room and occasionally ask her questions to ensure she understands directions and material. If Martha begins to daydream, her teachers gently remind her to focus. She has also been working with Mr. Banks to develop self-monitoring techniques. Martha has been using her extra time accommodation and her grades have been steadily improving. Her school recently hosted a professional development session on best practices for educating twice-exceptional students. Martha’s friends, family, and educators have noticed an improvement in her academic performance and overall well-being, and Martha is relieved to finally be feeling like herself again.

Discussion Questions

- Although Martha has demonstrated high achievement throughout high school, what recent behaviors indicate that she may need additional academic and socioemotional support now?

- What are some factors that may have caused Martha’s family and teachers to overlook the signs that she was experiencing a learning challenge (ADHD)?

- Research supports the use of strengths-based interventions with students who are twice-exceptional. What strengths-based, asset-focused approaches might be appropriate for Martha in her academic coursework, extracurricular activities, social interactions, and at home?

Case Study Notes

Focus: A high school junior in a suburban school shows marked changes in her academic achievement and social interactions.

Key points:

- Martha is struggling academically and in her peer relationships.

- Her friends and family are supportive of her academic and extracurricular efforts.

- Those close to Martha are concerned that she has not been acting like herself.

- Martha’s school psychologist and primary care physician were consulted as part of the evaluation process.

- Martha’s cognitive assessment suggests she is high achieving, which has led to some confusion about which services she needs.

Potential discussion topics:

- Twice-exceptionality

- ADHD in girls

- Identifying advanced learning needs

- Identifying other learning challenges

- Masking (when one exceptionality makes another exceptionality more difficult to identify)

NAGC Standards

- 1.1. Self-Understanding. Students with gifts and talents recognize their interests, strengths, and needs in cognitive, creative, social, emotional, and psychological areas.

- 1.5. Cognitive, Psychosocial, and Affective Growth. Students with gifts and talents demonstrate cognitive growth and psychosocial skills that support their talent development as a result of meaningful and challenging learning activities that address their unique characteristics and needs.

- 2.1. Identification. All students in Pre-K through grade 12 with gifts and talents have equal access to the identification process and proportionally represent each campus.

- 2.2. Identification. Students with gifts and talents are identified for services that match their interests, strengths, and needs.

Texas State Plan Standards

- Student Assessment: Gifted/talented identification procedures and progress monitoring allow students to demonstrate and develop their diverse talents and abilities.

- 2.4 Families and staff are informed of individual student assessment results and placement decisions as well as given opportunities to schedule conferences to discuss assessment data.

- 2.5 An awareness session providing an overview of the assessment procedures and services for gifted/talented students is offered for families by the district and/or campus prior to the referral period.

- 2.29 Student progress/performance in response to gifted/talented services is periodically assessed using standards in the areas served and identified in the written plan. Results are communicated to parents or guardians.

- Service Design: A flexible system of viable service options provides a research-based learning continuum that is developed and consistently implemented throughout the district to meet the needs and reinforce the strengths and interests of gifted/talented students.

- 3.1 Identified gifted/talented students are assured an array of learning opportunities that are commensurate with their abilities and that emphasize content in the four (4) foundation curricular areas. Services are available during the school day as well as the entire school year. Parents are informed of these options (19 TAC §89.3(3)).

- Family/Community Involvement: The district involves family and community members in services designed for gifted/talented students throughout the school year.

- 6.2 Input from family and community representatives on gifted/talented identification and assessment procedures is invited annually.

TEMPO+ Resources for Additional Reading

Boswell, C. (2018, February). The evaluation journey. TEMPO+. https://tempo.txgifted.org/the-evaluation-journey

Fugate, C. M. (2019, May). Increasing the visibility of the needs of girls who are gifted with ADHD. TEMPO+. https://tempo.txgifted.org/increasing-the-visibility-of-the-needs-of-girls-who-are-gifted-with-adhd

Case Study 6: Balancing Assessment, Feedback, and Student Motivation

Carol M. Raymond

Alzada Academy began a decade ago as a school-within-a-school magnet program created to meet the needs of highly gifted students within a large suburban school district. The program started with fifth and sixth grades and grew to accommodate a new grade level each year. The program has a holistic admissions process that uses multiple sources of data, including cognitive and achievement assessments; parent, teacher, and student inventories; a portfolio submission; and a student interview. Open enrollment transfers from nearby school districts are also allowed. In the first few years, the program’s focus was to help students love learning again. Many of the children who enrolled were burned out and tired of busy work. Most students who transferred to the program during the first few years were from a local school district that had recently made substantial cuts to gifted and talented programming. These students were used to reading multiple novels a week after finishing their assigned work and had few opportunities for enrichment.

During the first years of the program, the instructors sought to cultivate curiosity and inquiry. Although the students still took state assessments, most were performing above grade level, so the emphasis on meeting state standards was relaxed in favor of open-ended projects. Rubrics included mastery indicators, but always added an above-and-beyond category that encouraged students to use their gifts and talents in creative ways. Academy students could attempt challenges without the risk of failure. Students had considerable input on discussion topics and class selection. Grades were awarded, but little attention was placed on report cards by teachers, students, or parents. Students earned high achievements in regional and state science fairs and in all levels of creative problem-solving competitions. They participated in active learning experiences through partnerships with local businesses and nonprofits. The academic progress of early cohorts was extraordinary and evident in everything from class discussions to projects.

However, this desire to explore without fear of failure slowly changed. The climate shifted when the initial group of sixth graders reached high school. Although students earned grades for their assignments throughout middle school, they now requested access to the online grade portal. There was a noticeable change from embracing inquiry and exploration to completing just enough work to get an A+. As such, the quality of work also diminished.

Another shift occurred when the school began offering AP courses and exams. Where students had previously tackled real-world problems and engaged with the curriculum in authentic ways, they now had timed writings and practice exams. Their stress levels skyrocketed. Many were concerned that if they didn’t take the AP courses and the AP exams, they would not be admitted to their top choice of college. Although the first few graduating classes chose unique postsecondary schools where they could continue learning through inquiry and exploration, later graduating classes began seeking admission to prestigious schools. As graduates enrolled in top-ranked postsecondary institutions, many students in Alzada Academy’s high school reported that they felt increased pressure to perform so they, too, could attend such competitive colleges.

Current Opportunity

Alzada Academy is undergoing a program review. Experts in gifted education have been consulted to serve on the school’s advisory board as they determine the best trajectory for the next decade. Members of the advisory board have been provided with:

- student learning artifacts across grade levels from the past 10 years;

- aggregate student performance data, including NWEA MAP, PSAT, ACT, and SAT scores;

- lists of postsecondary schools at which graduates have matriculated; and

- transcripts of alumni interviews.

Three potential changes have been recommended:

- Limit the number of AP courses students are permitted to take each year. This number would be reported to institutions of higher education in the secondary school profile, so students would not face negative repercussions for this change.

- Transition to a mastery-based transcript to encourage inquiry, creativity, and risk-taking.

- Eliminate class rank for high school students.

The alumni interviews revealed a few key themes:

- Once students began AP courses, they felt like they did not have as much time for creative projects as they had before.

- Students noted that the AP Seminar and AP Research classes did prepare them for postsecondary academic writing and research.

- A few former students highlighted the benefit of receiving college course credit for their AP exams, but some said that the credit did not significantly change their college course load.

- Former students thought mastery grading could be one way to increase motivation and engagement in assignments.

- Some suggested that eliminating class rank could help alleviate the pressure to excel across all subject areas and provide greater freedom to specialize and explore their interests.

Discussions with faculty members have yielded similar themes. Many of them miss the energy that was present when students had the freedom to be more creative, self-directed learners. Most teachers would rather have one-on-one coaching sessions to give feedback instead of number or letter grades. Students already create portfolios to show their progress, so the change to mastery grading would not be a significant difference. The dean of the program is concerned about how college admissions will be affected if the school limits its AP curriculum. However, the dean also realizes that the change would allow students to focus more on their talent development courses, which include opportunities to explore interests and engage in mentorships and internships. The dean is also unsure what ramifications a non-traditional transcript might have for future graduates. Parents are split in their opinions about changes to the curriculum and transcripts. Some agree that the proposed changes would provide more freedom for exploration and authentic learning, while others fear that the changes will negatively affect their student’s college prospects. The school has the opportunity to make some changes based on the feedback from students, alumni, educators, and families, but school leaders aren’t sure where to start to help students recapture the love of learning.

Discussion Questions

- How can traditional grading policies impact student creativity, curiosity, and achievement?

- How could mastery-based grading support intrinsic motivation to learn?

- How can schools and families work together to help students make decisions about the amount of advanced-level coursework they take on each year?

- Discuss the role that AP courses play in a student’s academic talent development trajectory.

Case Study Notes

Focus: A school notices a change in student motivation and looks at several possible solutions.

Key points:

- Traditional grading practices may lead to unintended consequences for secondary students with advanced learning needs.

- Students who choose to take the most challenging courses offered by their schools may flourish, but some may also need guidance to consider other factors (e.g., cumulative load, extracurricular activities, mental health).

- Students may experience barriers (e.g., time, fatigue, stress, lack of opportunity) that discourage engagement in creative or exploratory endeavors.

Potential discussion topics:

- The role of grades for students with advanced learning needs

- Balancing rigor and responsiveness in advanced-level coursework

- College admissions requirements

- Mastery-based grading

NAGC Standards

- 1.5. Cognitive, Psychosocial, and Affective Growth. Students with gifts and talents demonstrate cognitive growth and psychosocial skills that support their talent development as a result of meaningful and challenging learning activities that address their unique characteristics and needs.

- 2.4. Learning Progress. As a result of using multiple and ongoing assessments, students with gifts and talents demonstrate growth commensurate with abilities in cognitive, social-emotional, and psychosocial areas.

- 3.2. Talent Development. Students with gifts and talents demonstrate growth in social and emotional and psychosocial skills necessary for achievement in their domain(s) of talent and/or areas of interest.

- 4.1. Personal Competence. Students with gifts and talents demonstrate growth in personal competence and dispositions for exceptional academic and creative productivity. These include self-awareness, self-advocacy, self-efficacy, confidence, motivation, resilience, independence, curiosity, and risk taking.

- 6.4. Lifelong Learning. Students develop their gifts and talents as a result of educators who are lifelong learners, participating in ongoing professional learning and continuing education opportunities

Texas State Plan Standards

- Service Design: A flexible system of viable service options provides a research-based learning continuum that is developed and consistently implemented throughout the district to meet the needs and reinforce the strengths and interests of gifted/talented students.

- 3.2 Information concerning special opportunities (i.e., contests, academic recognition, summer camps, community programs, volunteer opportunities, etc.) is available and disseminated to parents and community members.

- 3.9 Local board policies are developed that enable students to participate in dual/concurrent enrollment, distance learning opportunities, and accelerated summer programs if available.

- Curriculum and Instruction: Districts meet the needs of gifted/talented students by modifying the depth, complexity, and pacing of the curriculum and instruction ordinarily provided by the school.

- 4.2 Opportunities are provided for students to pursue areas of interest in selected disciplines through guided and independent research.

TEMPO+ Resources for Additional Reading

References

Boswell, C., & Weber, C. L. (2022, July). Modeling the use of case studies to support productive professional learning. TEMPO+.https://tempo.txgifted.org/modeling-the-use-of-case-studies-to-support-productive-professional-learning

Dixson, D. D., Peters, S. J., Makel, M. C., Jolly, J. L., Matthews, M. S., Miller, E. M., Rambo-Hernandez, K. E., Rinn, A. N., Robins, J. H., & Wilson, H. E. (2020). A call to reframe gifted education as maximizing learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 102(4), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721720978057

Ford, D. Y., & Grantham, T. C. (2003). Providing access for culturally diverse gifted students: From deficit to dynamic thinking. Theory Into Practice, 42(3), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4203_8

Meyer, M. S., Shen, Y., & Plucker, J. A. (2023). Reducing excellence gaps: A systematic review of research on equity in advanced education. Review of Educational Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543221148461

National Association for Gifted Children. (2019). 2019 Pre-K–Grade 12 Gifted Programming Standards. http://www.nagc.org/sites/default/files/standards/Intro%202019%20Programming%20Standards.pdf

Plucker, J. A., & Callahan, C. M. (2020). The evidence base for advanced learning programs. Phi Delta Kappan, 102(4), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721720978056

Plucker, J. A., & Peters, S. J. (2016). Excellence gaps in education: Expanding opportunities for talented students. Harvard Education Press.

Texas Education Agency. (2019). Texas state plan for the education of gifted/talented students. https://tea.texas.gov/Academics/Special_Student_Populations/Gifted_and_Talented_Education/Gifted_Talented_Education

Weber, C. L., Boswell, C., & Behrens, W. A. (2016, May). Providing quality professional development utilizing case studies. TEMPO+. https://tempo.txgifted.org/providing-quality-professional-development-utilizing-case-studies

About the Authors

Melanie S. Meyer, Ph.D., is a lecturer at Baylor University in the Learning and Organizational Change Ed.D. program. She holds a Ph.D. in educational psychology with a concentration in gifted and talented education from the University of North Texas and was a postdoctoral research fellow at Johns Hopkins University. She was a classroom teacher in Texas for more than 20 years, with experience in analytical reading and writing development in gifted and advanced academic settings. Her research focuses on equitable education policy, school-based creativity and talent development, and the postsecondary choices (e.g., college, career, military service) of talented students.

Rebecca M. Wessman is a graduate student at Baylor University in the Master of Arts in Teaching program with a focus on twice-exceptionality. She also holds a Bachelor of Science in elementary education from Baylor University. She has coedited two collections of instructional case studies for teacher professional learning on advanced learning needs and twice-exceptionality.

Chloe M. Thomas is a graduate student at Baylor University in the Master of Arts in Teaching program with a focus on twice-exceptionality. She holds a Bachelor of Science in elementary education from Baylor University and will begin her teaching career in the Frisco Independent School district with second-grade students. She has coedited two collections of instructional case studies for teacher professional learning on advanced learning needs and twice-exceptionality.

Mackenzie Stewart is a graduate student in the School Psychology program at Baylor University. She also has a Bachelor of Science in family and consumer science from Baylor University. She has worked in early childhood education and is currently an assistant preschool teacher at the Piper Center for Family Studies and Child Development.

Madeleine G. Boschen is a graduate student at Baylor University working toward a Master of Science in Education in educational psychology with a concentration in gifted and talented education. She also holds a Bachelor of Science in elementary education with a concentration in gifted and talented education from Baylor University. Madeleine is currently researching and designing curriculum standards for gifted and talented programming.

Hailey D. Short, B.S.Ed., is a graduate student pursuing her educational specialist degree in school psychology at Baylor University. She holds a B.S.Ed. in special education from Loyola University Chicago. She completed her student teaching experience at a selective-enrollment high school in Chicago Public Schools, where she taught in both inclusion and self-contained classrooms. Her primary research interests are related to childhood trauma, and she is particularly interested in researching the effective implementation of trauma-informed care in schools.

Carol M. Raymond, M.Ed., is a Ph.D. student at Baylor University in school psychology. She holds a master’s degree in gifted education, an educational diagnostician certification, and a certificate in college counseling. Previously, Carol served as the Director of Assessment and College Advising at E.A. Young Academy, where she developed the school’s talent development program and taught courses, such as AP Research, AP Seminar, and Applied Research and Statistics. As a private consultant, Carol provides psychoeducational assessment, college and career consulting, personalized tutoring, and parent and educator training. Carol’s current research focuses on the intersection of creativity and religion. She is also interested in exploring machine-learning applications within academic assessments and interventions.