This article provides a brief overview of the current works of various associations and researchers in the field related to professional learning. Specific connections are made to the use of case studies aligned with the 10 Global Principles for Professional Learning in Gifted Education (World Council for Gifted and Talented Children [WCGTC], 2021). An introduction to a case regarding a twice-exceptional learner is then presented followed by modeling the use of various strategies on how to unpack, analyze, and solve a case to support productive professional learning.

How Do the Various Efforts of the Different Associations in Both General and Gifted Education Help to Define Productive Professional Learning?

Learning Forward, a national professional learning association, identified seven Standards for Professional Learning in 2011 and the characteristics that lead to effective teaching practices, supportive leadership, and improved student results. These standards are currently undergoing a revision with a continuous focus on improving educator practices and student outcomes. The Learning Forward website (https://learningforward.org) provides information about the 10 newly revised practices that emphasize rigorous content at a deeper level, conditions for success, and transformational processes. The site also describes the role of coaching and feedback to better support teachers as part of developing this expertise and enhancing the professional learning process.

Additional research substantiates elements of effective professional learning. Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) conducted a meta-analysis of more than 35 studies that examined the link between professional learning, teaching practices, and student outcomes, and provided insight into features of high-quality professional learning. The authors determined that effective professional learning is content-focused, includes active learning, involves collaboration, uses effective models, provides coaching and expert support, allows for feedback and reflection, and is of sustained duration.

There has also been an evolution of professional development in the field of gifted education. In 2013, the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) identified a professional development standard in its Pre-K–Grade 12 Gifted Programming Standards. In 2018, the Professional Development Network of NAGC requested an official name change to the Professional Learning Network, citing current trends that pushed for a designation that encompassed on-going reflective practices as opposed to development, which is reflective of a single session workshop. The term professional learning represents a progression in this thinking—an interactive, more modernized approach to continual education for practitioners (Western Governors University, 2014). Additionally, when updates were made to the Pre-K–Grade 12 Gifted Programming Standards (NAGC, 2019), the standard was renamed Professional Learning. The student outcomes that are used to assess the effectiveness of this professional learning standard continue to focus on talent development, lifelong learning, ethics, psychosocial and socioemotional development, and a new outcome of equity and inclusion. Even more recently, WCGTC (2021) released its 10 Global Principles for Professional Learning in Gifted Education. These principles were tiered content, evidence-based, holistic, broad, equitable, comprehensive, integral, ongoing, sustainable, and empowering.

Similar themes are found throughout these organizations and current research, thus providing the guidance and impetus for rethinking and questioning how professional learning has been previously offered. Table 1 provides an overview of how implementing case studies for productive professional learning aligns with the 10 WCGTC principles.

Table 1

Implementing Case Studies for Professional Learning Aligned With the World Council of Gifted and Talented Children Global Principles

| World Council of Gifted and Talented Children Global Principles in Professional Learning (2021) | Implementing Case Studies for Professional Learning |

| 1. Tiered Content | Professional learning should be tiered to address teachers’ varied levels of knowledge, content background, understanding of how to teach the content, and the contexts for teaching.Case studies can be used with various audiences. By using data from a needs assessment, differentiated learning experiences can be designed and implemented to provide motivation and engagement of all participants. |

| 2. Evidence-Based | Professional learning should be guided by best practice and research about identifying and meeting the needs of gifted learners.Unpacking, analyzing, and solving a case can help to better understand and apply evidence when recommending any course of action. |

| 3. Holistic | Professional learning should include meeting the academic, social, and emotional needs of gifted children.Case studies can help explore these needs for diverse learners in various settings. |

| 4. Broad | Professional learning should emphasize different levels and forms of giftedness and service options.Case studies provide an opportunity to explore various issues that may be specific to a classroom, school, or district. |

| 5. Equitable | Professional learning should emphasize knowledge about teaching diverse learners.Providing case studies that emphasize issues in equity can encourage reflection about personal and professional practice while also considering the use of an equity lens for examining beliefs and practices with the school or district. |

| 6. Comprehensive | Professional learning plans should include administrators, counselors, psychologists, and other professionals and stakeholders.Requiring participants to view the issues in a case from the lens of various perspectives provides opportunities to think outside the box. |

| 7. Integral | Professional learning should be provided to all levels of the school community to increase awareness and service options to learners who are gifted.Case studies can be tailored to meet the specific needs of local districts. |

| 8. Ongoing | Professional learning should build on prior knowledge and lead to future learning and reflection.Because case studies encourage active engagement in discussions including decision making and problem solving, coaching and mentoring can be encouraged with opportunities for feedback and self-improvement. |

| 9. Sustainable | Professional learning plans should be tied to state, district, and school initiatives. Examining case studies can encourage collaboration of all stakeholders in problem solving and reinforce the need for accountability of programs and services. |

| 10. Empowered | Professional learning should result in educators being empowered to continue to advocate for gifted education and talent development.Case studies provide opportunities for participants to make decisions and provide solutions for problems that can lead towards change. |

Case studies facilitate both analysis of a student’s needs or school situation and critical reflection regarding current issues. Analysis and critical reflection must include knowledge of the scenario and application of the most current research relevant to the stated issue or issues. For example, a case study that outlines the learning strengths and learning differences of a twice-exceptional student provides the opportunity for local educators to analyze the situation and determine the best course of action by first using the student’s strengths to develop learning differences. It is important for these educators to apply their problem-solving and decision-making skills as they search for alternative strategies for teaching and learning that rely on sound research and best practices in order to create outcomes beneficial to the students, the parents/guardians, and the educators involved with the student.

Case Study

The following case related to a twice-exceptional learner is provided along with various strategies on how to unpack and analyze a case.

Hunter

Hunter is a 16-year-old boy who is well-liked by his peers and his teachers. He has always made the honor roll, even though he doesn’t make studying the focus of his life. He is athletic, plays tuba in the band, is on the student council, and works part-time at the local grocery store.

So, what could be wrong? Nothing, unless you know how hard he struggles with all the reading for his Advanced Placement (AP) English and U.S. History classes. Hunter doesn’t tell others of his struggles because everyone thinks he can do anything. Band and athletics are important for him because they don’t require intensive reading and he can be successful in these endeavors. Math and science are good because they are concrete and often hands-on. AP U.S. History is okay because they have class discussions. He listens well and can pick up on what the content is, reread it at night, and be ready for further discussions and tests. English is the hardest because although he likes the literature and listens to the book on Audible when he can, he can’t pinpoint passages from the book when asked because he has only heard it. Grammar is okay, but writing is another struggle for him. He could draw what the teacher wants him to write; in fact, he could cartoon it because he is very good at cartooning.

Until now, the teachers and his parents haven’t noticed Hunter’s struggles with reading. He has masked his inability to read through cartooning and discussions.

Discussion Questions

- In what ways do Hunter’s abilities mask his struggles?

- How might Hunter’s learning differences be used to his advantage?

- What steps could be taken in a conference with Hunter, his parents/guardians, and school personnel?

Strategies for Unpacking a Case

The process for using a case study to enhance professional learning may take any one or a combination of these approaches (Weber et al., 2014). These approaches facilitate a deeper discussion of the questions provided above.

Approach 1. Focus, Issues, and Factors (see Figure 1). In order to approach the case study using Focus, Issues, and Factors, it may be helpful to complete the following process:

- Begin by understanding the case. Read the scenario carefully. Focus on the key facts that would impact your comprehension of the issue(s). Be sure to identify the 6 W’s (who, what, when, where, why, and to what extent) in your discussion. Consider role modeling various perspectives of different stakeholders.

- Answer the suggested questions for the case. List any other questions you have concerning the case. Record what you find interesting. Respond to questions posed if possible. Some questions may remain unanswered.

- After summarizing the key facts, try to narrow down a possible issue(s) or problem(s). Be sure to consider other factors (e.g., cultural, economic, pedagogical) that might influence the events in the scenario. If necessary, discuss resources needed to help further the analysis.

- Generate possible solutions to the problem. Determine the need for criteria to weigh possible solutions such as time, costs, level of impact, etc. Evaluate the alternative solutions using the criteria selected. Draft a plan of action as necessary. Present your findings to a larger group (Weber et al., 2014).

Figure 1

Focus, Issues, and Factors

FOCUS:

Who: Hunter, teachers, parents, peers

What: Determine the most important issue for Hunter. Is it reading ability? Is it focusing on his extracurricular activities? Is it matching his gifts to his struggles?

ISSUES:

Primary: Reading? Gifted abilities?

Secondary: Time spent on homework? Focus on cartooning?

FACTORS:

Cultural: Emphasis on sports, music, leadership? Twice-exceptionality?

Other: Time, effort, his strengths?

Adapted from Exploring critical issues in gifted education: A case studies approach, by C. L. Weber, C. Boswell, and W. Behrens, 2014, Prufrock Press.

Approach 2. Another strategy for analyzing a case expands the first method with more information about the details of the process. Determine the following:

- Who is the focus of the case study? In determining the focus of the study participants will see that many perspectives may be considered. When one person or entity is the focus, the issues involved will become clearer.

- What is the primary issue to be addressed? The primary issue is one that requires participants to aim toward a course of action.

- Is there a secondary issue? Secondary issues may include others involved, research that reveals another perspective to be considered, or additional information from secondary sources, such as the following:

- What cultural factors impact this case study (e.g., socioeconomic status, limited language proficiency, ethnicity, traditions, values/beliefs, family setting, community norms)?

- What other factors are relevant to the case study (e.g., evidence of special abilities, mental and physical health limitations or concerns, safety, learning differences, learning style, access to services, motivation, engagement, achievement)?

- With whom could you collaborate to resolve the issue(s)? Who, beyond the participants studying the case, could add insight into the issue? Parents? Former teachers familiar with the person or entity? Other students? University professionals?

- What course of action would you recommend? At this point, participants determine one course of action. This course must include this information:

- What research supports your recommendation? What are best practices to be included in your recommendation?

- What additional information or resources would be helpful? (Weber et al., 2014, p. 8)

Consider the solution after looking at research and additional information. Should the solution be adjusted or totally reformed? It may be important to look at points found in Approach 3 as participants work through Approach 2.

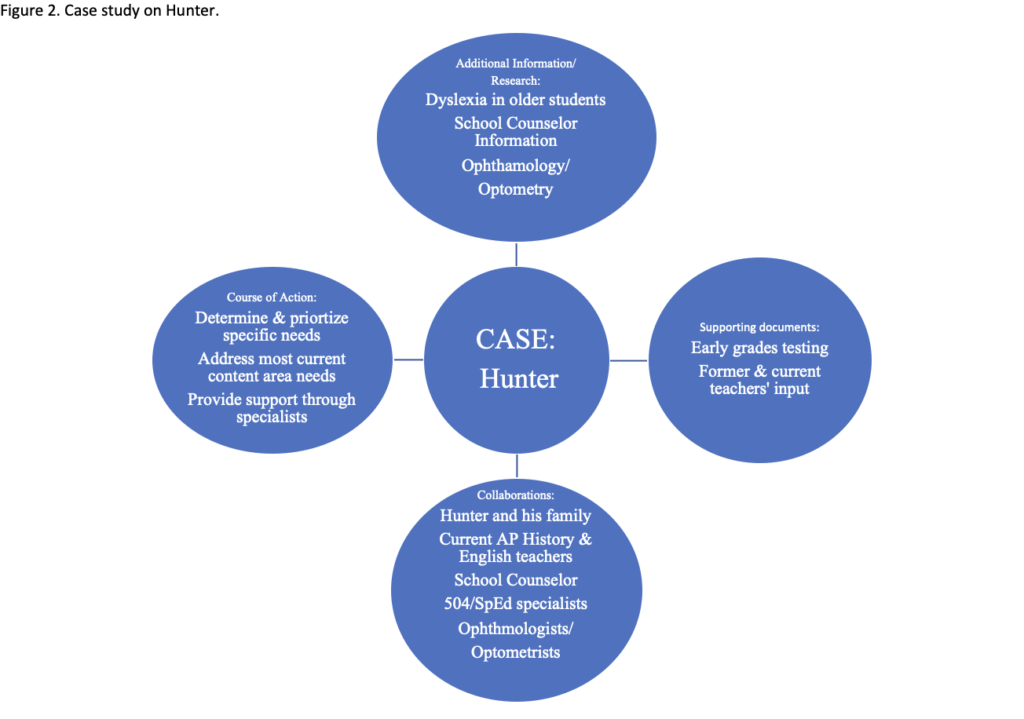

Approach 3. A third approach that takes the group to a final conclusion and evaluation of their decision(s) includes these questions (see Figure 2). (Note: Approach 3 could be helpful in conjunction with Approach 2 as a solution is formed.)

1. What makes a decision necessary?

2. What are my options?

3. What are the likely consequences of each option?

4. How important are the consequences?

5. Which option is best in light of the consequences? (Swartz & Parks, 1994)

Figure 2 is a graphic representation that facilitates understanding the case. This radial supports the decisions by including additional information and research, along with supporting documents and collaborations. This radial also illustrates the circular method that allows participants the freedom to reconsider and readjust earlier analyses and solutions.

Helpful Resources Supporting Case Studies

Weber, C. L., Behrens, W. A., & Boswell, C. (2016). Differentiated instruction for gifted learners: A case studies approach. Prufrock Press.

Weber, C. L., Boswell, C., & Behrens, W. A. (2014). Exploring critical issues in gifted education: A case studies approach. Prufrock Press.

Final Thoughts

We have an opportunity to rethink how to provide the most productive forms of professional learning in order to improve the teaching practices of educators working with gifted learners, improving student outcomes, and addressing student academic growth. What steps will be taken to revisit how we provide this professional learning? In what ways will professional learning opportunities be developed to support the research and best practices in the field? How can educators be empowered by their professional learning experiences? As suggested, using case studies as a focus for engaging and ongoing and sustained discussions can lead to more productive professional learning opportunities that support meeting the diverse needs of gifted learners.

References

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M., Gardner, M., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. https://learning policy institute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev

National Association for Gifted Children. (2019). 2019 Pre-K–Grade 12 Gifted Programming Standards. http://www.nagc.org/sites/default/files/standards/Intro%202019%20Programming%20Standards.pdf

Swartz, R. J., & Parks, S. (1994). Infusing the teaching of critical and creative thinking into content instruction: A lesson design handbook for elementary grades. Critical Thinking Books & Software.

Weber, C. L., Behrens, W. A., & Boswell, C. (2016). Differentiated instruction for gifted learners: A case studies approach. Prufrock Press.

Weber, C. L., Boswell, C., & Behrens, W. A. (2014). Exploring critical issues in gifted education: A case studies approach. Prufrock Press.

Western Governors University. (2014). Professional development vs. professional learning. https://www.wgu.edu/blog/professional-development-vs-professional-learning-teachers1712.html#openSubscriberModal

World Council for Gifted and Talented Children. (2021). Global principles for professional learning in gifted education. https://world-gifted.org/professional-learning-global-principles.pdf

Learn More About the Authors

Cecelia Boswell, Ed.D. taught migrant and gifted students, served as the Advanced Academics consultant for ESC-14, and the executive Director of Advanced Academics for Waco ISD. She is a consultant in district evaluation of gifted services and professional learning in gifted education and leadership nationally and throughout Texas. Dr. Boswell served on the TAGT Board of Directors, as TAGT President, and as President of the CEC-TAG. She has co-authored six books, including a chapter in an upcoming book by Susan Johnsen and Joyce VanTassel-Baska.

Christine L. Weber, Ph.D., is a professor at the University of North Florida. She has been a member of the Editorial Review Board for Gifted Child Today since 1998. Dr. Weber has published numerous articles and presented at state, national, and international conferences. She served as the Representative Assembly for CEC-TAG and Chair for the NAGC Professional Learning Network. Her recent books with coauthors include Differentiating Instruction for Gifted Learners: A Case Studies Approach and Exploring Critical Issues in Gifted Education: A Case Studies Approach. She has also co-edited an NAGC series on Best Practices in Professional Learning and Teacher Preparation.