By Adelle McClendon

This commentary was originally published in Spring 1991 as the “From the President” column in Volume XI, Issue 2, of TEMPO.

Recently, a colleague asked me a series of questions which reflected his obvious negative feelings toward the gifted and talented. As I responded, I took a firm stand on what I know to be true about the education of the gifted. I took an equally firm stand against prejudices, misconceptions, and misinterpretations which have harmful effects on the gifted. Five of the issues I can no longer stand for follow.

- I will no longer stand for the misinterpretation and misuse of “research” as it supposedly applies to the gifted.

For example, I can no longer stand by while “experts” espouse that any one grouping pattern is good for all students at all times—that we, indeed, want what is best for all students including the gifted. In other words, I will stay informed so that I can respond as a prepared professional. - I will no longer stand for the abuse of gifted students’ time to learn.

The overuse of gifted students as peer coaches, tutors, group leaders, and role models takes away from the time they need to learn what is new and appropriate for them. In fact, I believe one of the reasons gifted students may not choose teaching as a profession is that they have been used as “teachers” for 13 years, and thus, use their university time to pursue other professions! I concede that valuable socialization skills are learned as students work as peer coaches. I affirm that valuable skills are learned in cooperative groups. But when gifted students are always the group leaders and always the peer coaches and always the role models, there is a problem. Gifted students need time to work with their age peers, with their intellectual peers, and alone. I will stand up for their right to do all three. - I will no longer stand for emotion-packed terms like elitism being used to justify why gifted students should not work together on a regular basis.

In 20 or so years of working with gifted students. I have found that elitism rarely occurs in classrooms of students who are challenged and stimulated by students of similar academic abilities. In fact, gifted students who are consistently “the best” in classrooms where they face no real challenges are much more likely to appear elitist. Roger Taylor reminds us that Matt Dillon must face Annie Oakley. I will follow Dr. Taylor’s lead in reminding people of the same. - I will no longer stand for the misconception that what is taught in classrooms for the gifted must necessarily be taught to everyone.

However. I will be the first to point to Dr. Jim Curry’s letter published in Education Week, which states that there are no gifted toys, games, or materials, and consequently, that special toys, games, and materials that are being saved for the gifted do not a program make! I will affirm that all students should learn to think, to be creative, and to be productive. I will concede that many of the strategies used with the gifted can and should be used with all students. However, appropriate education for the gifted responds to the similarities as well as to the differences of gifted students and their age peers. As gifted students are like their age peers, they should be taught like their age peers. As they are different, they should be taught differently. I will be knowledgeable, specific, and prepared in my understanding of what is appropriate for all students and what is, indeed, most appropriate for the gifted. - I will no longer stand for a lack of understanding of what it takes to be a quality teacher of the gifted.

People who believe that teaching the gifted is easy are misinformed, naive, or both. The appropriate teaching of the gifted is as challenging as the appropriate teaching of any special students. Teachers of the gifted need special training to understand the students they are charged to teach. They also need recognition for their dedication to teaching students who challenge and question everyone and everything. Teaching the gifted is as tiring and draining as it is rewarding. It is time to stand up for the teachers who give endlessly in meeting the needs of our students.

My challenge to you is to consider what you stand for in the education of the gifted. Equally important, I challenge you to consider what you can no longer stand for. In so doing, we will all function as stronger advocates for our gifted and talented students.

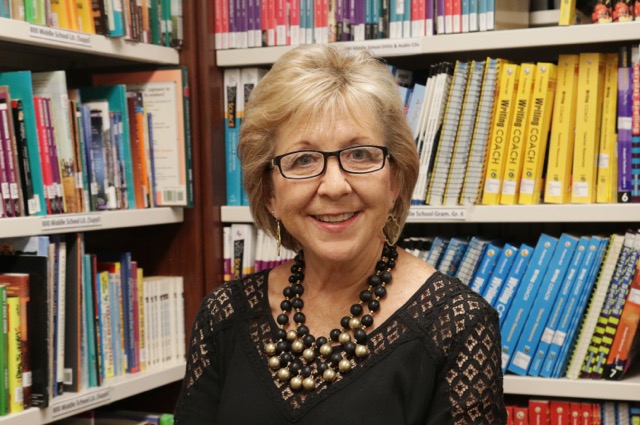

Adelle McClendon, President of TAGT in 1991, served as the Coordinator of Gifted Programs for Cypress-Fairbanks ISD and was very involved in the Texas Academic Decathlon and the Odyssey of the Mind competitions. Adelle passed away as a result of a car accident in 1995. That Saturday morning, she was on her way to judge a competition in which gifted students were competing. The story is shared that she told the EMT staff helping her at the scene of the accident that they needed to get her to the competition . . . that kids were counting on her. TAGT has established a scholarship in Adelle’s name to honor her passion, work, and love for gifted kids.