Teachers are the most influential in-school factor in student learning improvement (Demie, 2012; Grisham, 2000; Hattie, 2009). With such a significant impact, we cannot ignore the repeated outcry from teachers that their professional development courses are not practical enough (Adoniou, 2013) for their career in education. As online learning becomes more prevalent for K–12 students, it is important for teacher professional development to model K–12 best practices in an online environment while keeping adult learner engagement at the forefront. Choosing the career of teaching is very personal, and we must take this into consideration as online professional development is created to best engage educators as learners at a personal level while also modeling the competencies of a successful teacher. For deep learning to occur, the online content and design must move beyond the isolation of course content as the sole focus and connect educators to the other contextual influences on their teaching.

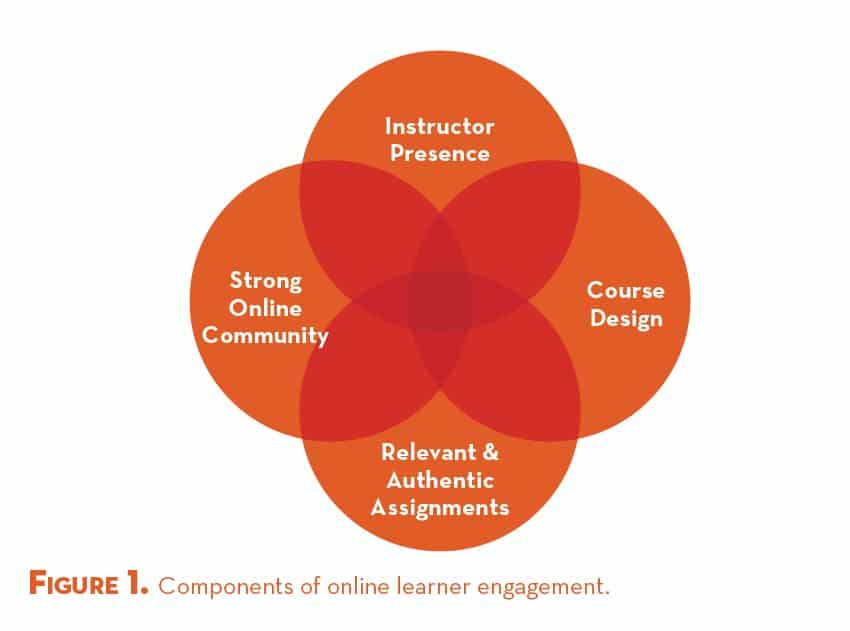

Although there are areas of overlap, best practices for learner engagement in traditional settings do not seamlessly transition to the online platform for educator training; however, we do know that student engagement is key for online learning to become internalized (Holzweiss, Joyner, Fuller, Henderson, & Young, 2014). Throughout the literature, four components of effective online learner engagement surface: instructor presence, course design, relevant and authentic assignments, and a strong online community (see Figure 1).

The Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2000) model, “Community of Inquiry,” described the three factors of online presence: cognitive, teaching, and social. Students are most engaged when they have consistent and individualized feedback with the instructor. Effective online teaching presence requires instructors to not only answer student’s academic questions, but also to hear their students’ stories, because doing so is part of the role of invested teachers and thus allows for personal connections to be made (Freeman & Wash, 2013). The Quality Matters K–12 Secondary Rubric also emphasized the importance of learner engagement and instructor presence, as these components are a quarter of their standards (MarylandOnline, Inc., 2015). The connections become vital to each student’s learning process, persistence, and perception of course quality. Students’ positive perceptions of the quality and level of interaction are strongly correlated to higher grades or course performance (Ginns & Ellis, 2007). This suggests that instructor presence is highly influential in student perspectives and success in online platforms for both adult and K–12 learners.

The course design can engage adult learners more readily by providing simple course navigation, organization that mimics the course syllabus, and self-directed tasks with clear directions and expectations (Casey & Kroth, 2013; Freeman & Wash, 2013). Concise directions and expectations can be further supported through instructor explanation via video/audio files and task exemplars. Using scaffolding techniques like navigation tips and a FAQ section allows learners to focus on the content and avoid the frustrations of learning the technology.

Although course design is important, Ginns and Ellis (2007) stated that “focusing on the (relatively) objective usability of a course website, for example, runs the risk of failing to understand how students understand the role of the site for learning at large” (p. 63). Learning new content and crafting their profession is the reason these learners have enrolled in the course. It is important that the course assignments are relevant and authentic to today’s educational best practices.

Learners become deeply engaged in their learning environment when it reflects their purposes, values, and interests (McGuckin & Ladhani, 2010). Adult learners should engage in active learning—cooperative grouping, team activities, guided inquiry, and integrated multidisciplinary tasks with real-world applications, reflection, and critical thinking—as well as experience multimodal approaches like drama, music, and humor throughout the lessons (Freeman & Wash, 2013; MarylandOnline, Inc., 2015; Waldner, McGorry, & Widener, 2012). Within the parameters of the course expectations, adult learners should be empowered to establish their own learning goals while receiving enough guidance to promote professional growth and challenge. Authentic assignments are not complete without self-reflection, which allows learners to critically analyze their application of the content presented and to respond to their peers’ ideas in the online community.

Online learners are more likely to contribute and interact in a “high expectations, but low-stress environment” (Freeman & Wash, 2013, p. 101). Schrum, Burbank, Engle, Chambers, and Glassett (2005) found that educators want professional development that not only directly ties to practice, but also moves them toward academic interactions with their colleagues. Online learners want a strong community to solidify their own learning in the course, and to extend their professional practice. This idea is echoed in Schrum, Burbank, and Capps’s (2007) study indicating that online teacher networks may increase teachers’ efficacy in meeting students’ needs. Teachers also expressed that the higher sense of their own efficacy made them more open to adopt new classroom behaviors and to stay in the profession.

Benefits and Issues of Online Professional Development

Online learning can provide benefits that may be limited in traditional settings. A rich and more equitable environment personalized to each learner is more attainable with the ability to communicate with all participants, not just those willing to speak out in a face-to-face class (Baghdadi, 2011). Peer and instructor-led online discussions are dependent on experiences and contexts that are relevant to the individuals, which allows learners to create personal relevancy (Baker, 2013). When freed of place-based constraints, professional collaboration can reach beyond regional, national, or even global borders (Waldner et al., 2012). With the ability to conduct online learning asynchronously or synchronously, peer and instructor accumulated knowledge and skills (based on discussion boards and interactive tasks) can be transmitted from current participants to future participants, bypassing the limitation of “in the moment” or face-to-face professional development (Baghdadi, 2011). Online professional development learners benefit from the flexibility of timing and e-mail interactions and the valuable and relevant content to their careers (Schrum et al., 2007). Due to the ability to work in the comfort of their chosen space, online students, by feeling socially comfortable, exhibit higher order skills in analysis and synthesis and discuss their ideas more freely (Baker, 2013; Freeman & Wash, 2013; Schrum et al., 2007). Students are more empowered during collaborative work because they become the decision makers for work distribution and group expectations (Casey & Kroth, 2013). Cerniglia (2011) found that students (both adult and K–12 learners) participating in online courses also express themselves more authentically due to alternative assignment choices. A meta-analysis of online learning experiments from 1996 to 2008 revealed that students in online learning courses performed better, on average, than face-to-face instruction in terms of course grade average and test results (Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia, & Jones, 2009). Means et al. (2009) also determined that the learning outcomes of online students surpassed the outcomes of students with traditional instruction with an effect size of 24%. This could be attributed, in part, to the fact that online learning is more conducive to the expansion of time on task over face-to-face instruction (Means et al., 2009).

Of course, there are drawbacks to online platforms for professional development. In a 2011 study, Faulk found that many teachers and administrators were concerned that, “nothing beats practical experience and the ability to learn by doing” (p. 84). Although online professional development may be convenient, face-to-face instruction provides social aspects that are critical in education and not always adequately supported in an online community (Schrum et al., 2005). Although students tend to be honest in an online platform, they may also be willing to express personal beliefs and bias that could be considered controversial in a face-to-face environment (Schrum et al., 2007). Also, some adult learners may prefer face-to-face interaction because a lack of reminders for assignment due dates, collaboration dependent on others’ time on task, and a dependence on unreliable technology may result in frustration (Schrum et al., 2007). In general, learner performance is highly related to one’s engagement level in any given course whether face-to-face or in an online environment (He, Xu, & Kruck, 2014). This reiterates the idea, discussed earlier, that the expansion of dedicated learning time in an online environment may be a factor that results in higher student achievement.

Online professional development can demonstrate many effective strategies for educators to implement in their classrooms with gifted students. To successfully support and challenge 21st-century gifted students, educators must strategically balance the relationship between content, pedagogy, and technology (Waldner et al., 2012). Holzweiss et al. (2014) characterized the best learner experiences as those that provide (a) academic challenge, (b) timely feedback, (c) a supportive environment, (d) regular interaction with the teacher, and (e) courteous interaction with peers. One can see how these mimic the cultivation of online learner engagement as mentioned earlier.

Teacher education courses are most effective when they provide both a framework for new conceptualizations and “challenging experiences that require learners to rethink their understandings based on evidence from experience” (Schrum et al., 2007, p. 210). This framework is not only best for educators, but it also provides the most stimulating foundation for gifted students to grow and thrive. Educators should be asked to creatively teach or apply concepts for peer review where classmates can question their research and opinions. This encourages all involved to synthesize a greater understanding of the content and provides a working example from which educators can translate the application process as a task for their gifted students. Educators may benefit from experiencing discussion boards that are founded in culturally diverse content, while being challenged to analyze the ideas presented through open-ended questions (Baker, 2013; MarylandOnline, Inc., 2015). Discussion boards cultivate learner connections with their peers and provide more awareness of others’ ideas (Cerniglia, 2011). Due to the difficulty of some gifted students in understanding social parameters, educators who implement this approach need to demonstrate the appropriate way to develop, clarify, or question their peers’ ideas and ensure that all students feel supported and comfortable posting their ideas, even when ideas are challenged (Cerniglia, 2011; Thiede, 2012).

Asynchronous online discussions support learners in self-direction of their learning through conducting additional research of personal interest to support a point or probing the experiences and ideas of others (Baker, 2013). Cerniglia (2011) has suggested that educators utilize peers’ strategies in their own classrooms, or adapt those ideas, to promote the value of learning from other practitioners and administrators. This is a skill that is invaluable for educators and gifted students alike; it is an important reminder that we do not have to obtain knowledge in isolation. Student-to-student and student-to-instructor interactions aid in the creation of personal relevancy (Baker, 2013).

Short video lectures connect learners with the instructor and offer another method to communicate the content in detail. Using multimodal means of communication supports greater understanding (Cerniglia, 2011; Thiede, 2012). Freeman and Wash (2013) pointed out that community is also created through humor, where students learn to laugh at their mistakes and notice how life, in and out of the classroom, is joyful. Both educators and gifted students can benefit from appreciating the fun of learning and daily life experiences to build comradery beyond their love for a subject area. This “relaxed alertness” creates a comfortable community that will encourage more participation and fosters feelings of self-confidence and motivation for all learners (McGuckin & Ladhani, 2010).

Curriculum and learning strategies are living plans, and therefore, both educators and professional development designers must acknowledge that the abilities and knowledge that their students are asked to master must continually change (Freeman & Wash, 2013). Both adult and K–12 students theoretically crave learning experiences that enhance their intellectual capacity, but further research demonstrates a need to create relevancy and a personal relationship with the subject matter (McGuckin & Ladhani, 2010). Similar to some educators’ preferences, Thomson (2010) has acknowledged that access to online courses with a more flexible, a more individualized, and a more student-centered approach to learning have the potential to be a particularly sound options for modeling how to serve gifted students and educators. The benefits of the online “teacher as a mentor” relationship include the use of a targeted tailoring of the content to individual needs (Thomson, 2010). Providing educators with this dynamic delivery of online best practices is a multifaceted model for serving students.

References

Adoniou, M. (2013). Preparing teachers—The importance of connecting contexts in teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38, 47–60.

Baghdadi, Z. D. (2011). Best practices in online education: Online instructors, courses, and administrators. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 12, 109–117.

Baker, D. L. (2013, June). Advancing best practices for asynchronous online discussions. Business Education Innovation Journal, 5, 11–21.

Casey, R. L., & Kroth, M. (2013). Learning to develop presence online: Experienced faculty perspectives. Journal of Adult Education, 42, 104–110.

Cerniglia, E. G. (2011, May). Modeling best practice through online learning building relationships. Young Children, 54–59.

Demie, F. (2012). English as an additional language pupils: How long does it take to acquire English fluency? Language and Education, 27(1), 59-69.

Faulk, N. T. (2011). Perceptions of Texas public school superintendents regarding online teacher education. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 8(5), 79–85.

Freeman, G. G., & Wash, P. D. (2013). You can lead students to the classroom, and you can make them think: Ten brain-based strategies for college teaching and learning success. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 24, 99–120.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2, 87–105.

Ginns, P., & Ellis, R. (2007). Quality in blended learning: Exploring the relationships between on-line and face-to-face teaching and learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 10, 53–64.

Grisham, D. (2000). Connecting theoretical conceptions of reading to practice: A longitudinal study of elementary school teachers. Reading Psychology, 21, 145–170.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

He, W., Xu, G., & Kruck, S. E. (2014). Online is education for the 21st century. Journal of Information Systems Education, 25, 101–105.

Holzweiss, P. C., Joyner, S. A., Fuller, M. B., Henderson, S., & Young, R. (2014). Online graduate students’ perceptions of best learning experiences. Distance Education, 35, 311–323.

MarylandOnline, Inc. (2015, June). Standards from the QM K–12 secondary rubric, second edition [PDF document]. Retrieved from http://www.qualitymatters.org

McGuckin, D., & Ladhani, M. (2010). The brains behind brain-based research: The tale of two postsecondary online learners. College Quarterly, 13(3). Retrieved from http://collegequarterly.ca/2010-vol13-num03-summer/mcguckin-ladhani.htm

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505824.pdf

Schrum, L., Burbank, M. D., & Capps, R. (2007). Preparing future teachers for diverse schools in an online learning community: Perceptions and practice. The Internet and Higher Education, 10, 204–211.

Schrum, L., Burbank, M. D., Engle, J., Chambers, J. A., & Glassett, K. F. (2005). Post-secondary educators’ professional development: Investigation of an online approach to enhancing teaching and learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 8, 279–289.

Thiede, R. (2012). Best practices with online courses. US-China Education Review, 2, 135–141.

Thomson, D. L. (2010). Beyond the classroom walls: Teachers’ and students’ perspectives on how online learning can meet the needs of gifted students. Journal of Advanced Academics, 21, 662–712.

Waldner, L. S., McGorry, S. Y., & Widener, M. C. (2012). E-service-learning: The evolution of service-learning to engage a growing online student population. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 16, 123–149.

Heather Vaughn, Ed.S., is a passionate advocate for gifted students with expertise in designing curriculum, implementing research-based strategies, and mentoring teachers to provide best practices for gifted and advanced learners. She holds graduate degrees from the University of Mississippi and the University of Georgia.