The underrepresentation of Black students in gifted and talented education (GATE) has been a pervasive sore spot and bane of existence for the field for decades. According to Ford (2013), Black students continue to be the most underrepresented student population at a rate of almost 50%, followed by Hispanic students at around 40%. Combined, this is tantamount to more than 500,000 Black and Hispanic students not receiving needed academic services. Ford (2011) and coauthors herein are concerned about these students underachieving and how this widens racial achievement and opportunity gaps nationally, locally, districtwide, and on school campuses.

In this article, we discuss the invaluable need to focus on equity and how culture matters in all aspects of GATE recruitment and retention efforts beginning in early childhood—identification and assessment, social-emotional and psychological needs and development, and curriculum and instruction.

It is essential that Pre-K–grade 12 educators understand that addressing underrepresentation must begin in the early grades and be cultivated throughout the grades with an intentional focus on (1) identification, testing, and assessment; (2) curriculum and instruction; (3) culture and classroom; (4) social-emotional development; (5) self-identity/cultural pride; and (6) family relationships. For more attention to these six components of culturally responsive education, see Ford (2011). Due to space limitations, we focus on the first three and embed comments about the others in the following sections.

The Importance of Valuing Cultural Diversity/Differences in Early Childhood Education Within GATE

We still live in a world that is not yet a place where all children matter and have “equitable learning opportunities” (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2019, p. 5) to take part in experiences to develop their gifts and talents. This is especially true within the context of early childhood education in which the representation of children’s cultural backgrounds, customs, ways of communicating, ways of celebrating traditions, and values are not always considered relevant by educators (Wright, 2018). This lack of responsiveness can be particularly disadvantageous for Black and Brown children when educators are unable and/or unwilling to recognize the promise, potential, and possibilities of underrepresented students. This lack of familiarity regarding cultural differences includes, but is not limited to, languages, literacies, and cultural practices that children of color bring to school.

We want every child, early on, to express comfort and joy with their cultural identities and the diversity of classmates and other groups of color. With the present and future in mind, we believe there is a dire need to design, create, and implement more culturally relevant curriculum and instruction that will cultivate the gifts and talents of underrepresented students in GATE while also promoting positive socioemotional development and ethnic/racial pride. This begins with a focus on quality early childhood programming that provides access to rigorous early learning experiences that are part of and extend the traditional curriculum. As described next, by quality, we mean curriculum and instruction that attends to the importance of culture and climate that is responsive in promoting academic rigor while maintaining an environment in which self-knowledge, self-esteem, self-identity, agency, and voice are valued.

High-Quality Early Childhood Matters for Priming the Pipeline to GATE

Unfortunately, all early childhood programs are not equal. Studies show that some children of color, particularly Black preschoolers, are the least likely to gain access to high-quality early care and education. Using results from the National Center for Education Statistics study of observational ratings of preschool settings, Barnett et al. (2013) reported that 40% of Hispanic and 36% of White children were enrolled in center-based classrooms rated as “high,” while only 25% of Black children were in classrooms with the same rating. Furthermore, 15% of Black children attended childcare centers ranked as “low”—almost 2 times the percentage of Hispanic and White children. Latinx and Black children in home-based settings were even worse off, with more than 50% in settings rated as “low” compared to only 30% for White children (see Dobbins et al., 2016).

As a result of such early educational disadvantages, the potential and gifts and talents of far too many Black students, Hispanic students, and students from low-income backgrounds are compromised. But, as professionals and advocates, we must not give up on these children. Instead, we must invest more time, effort, and resources to identify, test, and assess—and then serve—this population. That is what equity is about.

Identification, Testing, and Assessment

Gifted and talented individuals are regarded as a small, select group, and young gifted children represent an even smaller group who are underserved. This is especially true for children of color. Although giftedness in young children is not well investigated and defined compared with older children, it is widely agreed that early recognition and identification of gifted children is important (National Association for Gifted Children, 2006; Pfeiffer & Petscher, 2008; Sankar-DeLeeuw, 2004).

In most states and districts, participation in GATE programs is influenced by two primary factors: parent/family advocacy and teacher/educator referrals. Although some districts have developed more comprehensive processes to identify and assess underserved populations, most districts rely on a subjective process to determine which students gain access to GATE (Ford, 2013; Grissom & Redding, 2016). Educator subjectivity, guided by deficit thinking and negative stereotypes, is the primary reason Black and Hispanic students are underrepresented in GATE (Ford, 2013).

To state the obvious, early recognition and identification are essential to help children learn during their primary years (Wortham & Hardin, 2015; Wright & Ford, 2017) and to prevent disengagement, underachievement, and negative attitudes toward school and GATE (Barnett et al., 2013; Ford, 2010; Puckett & Black, 2008). This is especially the case for children from low-income and racially, linguistically, and culturally different backgrounds. Heath’s (1989) assertion remains relevant today: These children often attend schools where teachers are “unable to recognize and take up potentially positive interactive and adaptive verbal and interpretative habits learned . . . within their families and on the streets” (p. 370). Consequently, children from low-income and non-White families who are unidentified at an early age are less likely to be recognized and served later.

Calculating Gifted and Talented Underrepresentation Using the Equity Allowance Formula

At the time of this writing, racial quotas are illegal; equity thresholds are not racial quotas. With quotas, group representation in school enrollment and GATE enrollment is proportional, meaning that if Black or Hispanic students comprise 42% of a school district (state or school building), they must comprise 42% of GATE enrollment.

We propose the following questions to serve as points of information when applying the Equity Allowance Formula (Ford, 2013): (1) When is underrepresentation significant? (2) How severe must underrepresentation be in order to require changes? (3) How severe must underrepresentation be to be discriminatory? While considering these questions, note that when the percentage of underrepresentation exceeds the designated threshold in the Equity Allowance Formula, it is beyond statistical chance; therefore, attitudes, instruments, and policies and procedures may be discriminatory and biased against underrepresented students.

To calculate the equity allowance goal, start with each group’s representation in the nation, state, district, or building. Then multiply that by 80%. To repeat, Black students make up 19% of the student population in our nation’s schools (Ford, 2013); 19% x .8 = 15.2%. Nationally, we must increase their representation in GATE programs from 10% to a minimum of 15.2%. Using the same formula, Hispanic students should be a minimum of 20% rather than 16% to be equitably represented in GATE nationally (see Ford, 2013).

Readers are also encouraged to read the Culturally Responsive Equity-Based Bill of Rights for Gifted Students of Color (Ford et al., 2018). It contains eight sections that can be used to evaluate GATE programs and services.

Cultural Attributes Matter in the Referral Process

For myriad reasons already stated, culture and cultural differences cannot be discounted and/or ignored in testing, assessment, identification, placement, and services, which Ford (2013) referred to as recruitment and retention. Educators must be culture conscious, not colorblind/cultureblind. As educators contemplate the future of GATE, they must do so by learning the cultural attributes and assets of their underrepresented students. As a framework, we use a Venn diagram to illustrate that all that is known about GATE students must be merged with the cultural attributes of students of color; they are gifted and culturally diverse and different.

We use the work of Boykin (1994, 2013) to describe the cultural characteristics and assets of Black students. Briefly, these include being movement-oriented and vervistic; field-dependent with a desire to feel welcome and valued in schools/classrooms; communal, whereby they are group-oriented with a preference for working cooperatively rather than competitively; creative, also known as expressive individualism; and possessing of a social time perspective in which time is viewed as endless and the current event is more important than the actual time. It behooves educators to learn more about the aforementioned cultural attributes of Black students and all students of color (Ford, 2011) in order to recruit, retain, and engage them in GATE.

Curriculum as Windows and Mirrors

Scholarship on the importance of a high-quality nonbiased, antiracist, multicultural, and culturally responsive curriculum is well documented (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2010; Ford, 2011; Kendi, 2019; Muhammad, 2020; Paris & Alim, 2017; Ramsey, 2015). For many students of color (of all ages), the curriculum is culturally irrelevant and unresponsive. One example is the selection of texts, materials, and standards, which generally center on White experiences and ways of existing and knowing in the world (Cridland-Hughes & King, 2015). When curriculum centers on Eurocentric/Westernized ways of thinking, being, and knowing, Black and other students experience the promotion of deficit-based ideologies, resulting in a form of epistemic violence that attacks Black and Brown students’ ways of knowing (Johnson et al., 2019). This epistemic violence also is a reminder to these students of color of what they are not, instead of their promise, potential, and possibility. The diversity of their languages, literacies, and cultural practices are frequently treated as problems to be fixed instead of resources to be tapped into.

We argue that the curriculum must be culturally responsive—recognizing that there are multiple ways of presenting and representing content that exposes students to their own culture and the culture of others in affirming (cultural pride) and authentic ways. Moreover, multicultural education cultivates strengths while recognizing the needs of students from culturally, linguistically, and economically different backgrounds. Therefore, the curriculum ought to present critical content as windows into the cultural worlds of others, while at the same time providing mirrors that affirm the views of students in general, including students of color (Bishop, 1990). Such a curriculum observes and documents students’ languages, literacies, and cultural practices. There is an astute recognition of the sociocultural knowledge and experiences students bring to the classroom. In other words, the curriculum listens to and values the stories and lived experiences of students. The histories and racial identities of students are central to planning curriculum and instruction and delivering culturally responsive instruction, with the ultimate aim of ensuring that underrepresented students are engaged in rigorous curriculum and learning, that they more fully understand and feel affirmed in their identities and experiences, and that they are equipped and empowered to identify and dismantle structural inequities.

Ford’s Bloom-Banks Matrix

Typically, when one hears the term differentiation, the work of Benjamin Bloom is the point of reference. However, when one speaks of a multicultural curriculum, a name of reference is not so readily apparent. We maintain that the work of James Banks (2009) should readily be in the conversation.

The curriculum must not only be rigorous, but also provide students with the ability to see the world from the viewpoints of others, and it must be relevant to students’ lives—their interests and experiences. Banks (2009) created a multicultural framework that allows teachers to infuse diverse components into daily lessons. Banks’s “no excuses” tool addresses four levels of integration ranging from the very simplistic and pervasive contributions approach, to the more complex and often neglected social action approach.

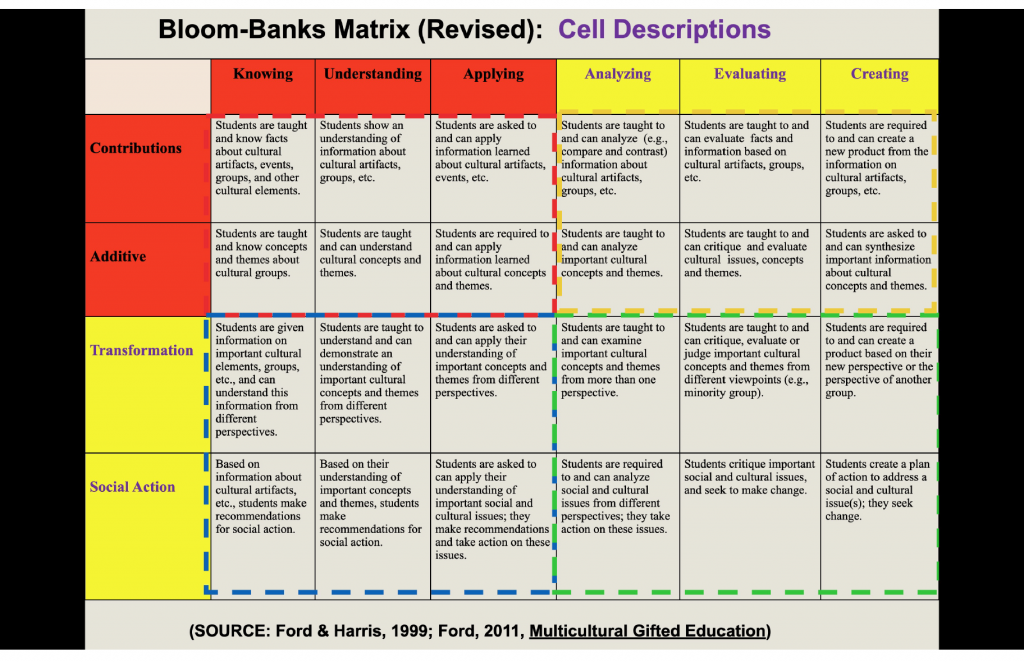

In 1999, Ford and Harris created a matrix that infuses Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy and Banks’s (2009) multicultural curriculum model. The Bloom-Banks Matrix, which was revised by Ford in 2011 and color-coded by Trotman Scott in 2014, combines Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives and Banks’s model to provide educators with a multicultural GATE model that is reflective of differentiated instruction that encompasses GATE and multicultural education. The result is 24 cells divided into four color-coded quadrants, based on the six levels of Bloom’s taxonomy and the four levels of Banks’s model (see Table 1). The lowest cell can be found in quadrant one, which is color-coded red, and the highest and most substantive cell is found in quadrant four, which is color-coded green. A description of the color-coded quadrants of the matrix follows.

Instruction in the red-colored quadrant provides content that is low on both Bloom’s taxonomy and Banks’s model. This quadrant is red in hue to signify that instruction should not stop in this quadrant. Content within this quadrant is familiar, meaning many students may have been exposed to similar information in previous settings. Because both rigor and cultural relevance are minimal in this quadrant, GATE students may not be challenged in either way (Trotman Scott, 2014).

Quadrant two, which is yellow in color to denote caution, ranks high on Bloom’s taxonomy but low on Banks’s model. Although lessons in this quadrant provide gifted students with the opportunity to think critically and solve problems, their multicultural content is superficial. Therefore, teachers should proceed with caution when teaching in quadrant two.

Instruction provided in quadrant three should be guarded; hence, the color assigned to this quadrant is blue. Low on Bloom’s taxonomy but leveled high on Banks’s model, the curriculum provided in this quadrant offers minimal critical thinking. However, students are provided with the opportunity to view cultural events, concepts, and themes through the lens of others.

The curricular goal is to provide instruction in quadrant four, which is color-coded green, indicating that the curriculum is on the go, and educators should aim to remain in this quadrant. High on Bloom’s taxonomy and Banks’s model, students are able to think critically, solve problems, and review a multitude of multicultural topics, issues, and themes as they seek to make social change through activism in some way. The curriculum is rigorous and relevant, students think and solve problems at the highest levels, and they are exposed to content that validates culturally different individuals and groups (Trotman Scott, 2014).

Summary

The underrepresentation of Black and Brown students in GATE programs is an equity issue and must be addressed to find defensible and culturally responsive solutions that will allow such students access to high-quality GATE program services. This access will go a long way toward narrowing achievement gaps and priming the GATE pipeline via a talent development approach that includes the valuing of cultural differences. When educators take into account the aforementioned considerations, many more Black and Brown students are likely to be recognized by educational professionals for their diverse gifts and talents. It is long overdue that we disrupt and interrupt inequities in GATE to ensure that no student’s intellectual, academic, creative, and artistic promise, potential, and possibility are diminished or ignored.

References

Banks, J. (2009). Diversity and citizenship education in multicultural nations. Multicultural Education Review, 1(1), 1–28.

Barnett, S., Carolan, M., & Johns, D. (2013). Equity and excellence: African-American children’s access to quality preschool. National Institute for Early Education Research. http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/CEELO-NIEERequityExcellence-2013.pdf

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix–xi.

Bloom, B. (Ed.). (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. Longmans Green.

Boykin, A. W. (1994). Afrocultural expression and its implications for schooling. In E. R. Hollins, J. E. King, & W. C. Hayman (Eds.), Teaching diverse populations: Formulating a knowledge base (pp. 225–273). State University of New York Press.

Boykin, A. W. (2013). On enhancing academic outcomes for African American children and youth. In Being Black Is Not a Risk Factor: A Strengths-Based Look at the State of the Black Child (pp. 28–31). National Black Child Development Institute.

Cridland-Hughes, S. A., & King, L. J. (2015). Killing me softly: How violence comes from the curriculum we teach. Rowman & Littlefield.

Derman-Sparks, L., & Edwards, J. O. (2010). Anti-bias education for young children and ourselves. National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Dobbins, D., McCready, M., & Rackas, L. (2016). Unequal access: Barriers to early childhood education for boys of color. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.childcareaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/UnequalAccess_BoysOfColor.pdf

Ford, D. Y. & Harris, J. J., III. (1999). Multicultural gifted education. Teachers College Press.

Ford, D. Y. (2010). Reversing underachievement among gifted Black students (2nd ed.). Prufrock Press.

Ford, D. Y. (2011). Multicultural gifted education (2nd ed.). Prufrock Press.

Ford, D. Y. (2013). Recruiting and retaining culturally different students in gifted education. Prufrock Press.

Ford, D. Y., Dickson, K. T., Lawson Davis, J., Trotman Scott, M., & Grantham, T. C. (2018). A culturally responsive equity-based Bill of Rights for gifted students of color. Gifted Child Today, 41(3), 125–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076217518769698

Grissom, J. A., & Redding, C. (2016). Discretion and disproportionality: Explaining the underrepresentation of high-achieving students of color in gifted programs. AERA Online, 2(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858415622175

Heath, S. B. (1989). Oral and literate traditions among Black Americans living in poverty. American Psychologist, 44(2), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.367

Johnson, L. L., Boutte, G., Greene, G., & Smith, D. (2019). African diaspora literacy: The heart of transformation in K–12 schools and teacher education. Lexington Books.

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One World.

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2019). Advancing equity in early childhood education position statement. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity

National Association for Gifted Children. (2006). Early childhood [Position statement]. https://www.nagc.org/sites/default/files/Position%20Statement/Early%20Childhood%20Position%20Statement.pdf

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (Eds.). (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Pfeiffer, S. I., & Petscher, Y. (2008). Identifying young gifted children using the Gifted Rating Scales—Preschool/Kindergarten Form. Gifted Child Quarterly, 52(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986207311055

Puckett, M. B., & Black, J. K. (2008). Meaningful assessments of the young child: Celebrating development and learning (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Ramsey, P. G. (2015). Teaching and learning in a diverse world: Multicultural education for young children (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

Sankar-DeLeeuw, N. (2004). Case studies of gifted kindergarten children: Profiles of promise. Roeper Review, 26(4), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190409554270

Trotman Scott, M. (2014). Using the Bloom-Banks matrix to develop multicultural differentiated lessons for gifted students. Gifted Child Today, 37(3), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076217514532275

Wortham, S., & Hardin, B. J. (2015). Assessment in early childhood education (7th ed.). Pearson.

Wright, B. L., & Ford, D. Y. (2017). Untapped potential: Recognition of giftedness in early childhood and what professionals need to know about students of color. Gifted Child Today, 40(2), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076217517690862

Wright, B. L. (with Counsell, S. L.). (2018). The brilliance of Black boys: Cultivating school success in the early grades. Teachers College Press.

Brian L. Wright, Ph.D., is an associate professor and program coordinator of early childhood education in the Department of Instruction and Curriculum Leadership in the College of Education and coordinator of middle school cohort of the African American Male Academy at the University of Memphis. His research examines high-achieving African American boys/males in urban schools (Pre-K–grade 12), racial/ethnic identity development of boys and young men of color, STEM and African American males, African American males as early childhood teachers, and teacher identity development. Dr. Wright is the author of the award-winning (2018 NAME Philip C. Chinn Book Award) and best-selling book The Brilliance of Black Boys: Cultivating School Success in the Early Grades (published in 2018 by Teachers College Press, Columbia University, https://www.tcpress.com/the-brilliance-of-black-boys-9780807758922?page_id=221).

Donna Y. Ford, Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor of Education and Human Ecology and Kirwan Institute Faculty Affiliate at The Ohio State University. She is in the Department of Educational Studies, Special Education Program. She earned all degrees from Cleveland State University. Ford focuses primarily on the underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic students in gifted education and advanced classes. She is well known as a leader in urban education. Dr. Ford has authored more than 350 publications and 14 books. She presents extensively in school districts and organizations nationally on opportunity gaps, equity, multicultural curriculum, antiracism, and culturally competent educators.

Michelle Frazier Trotman Scott, Ph.D., is the director of graduate affairs and a professor of special education in the College of Education at the University of West Georgia. Dr. Scott’s research interests include the opportunity gap, overrepresentation in special education, underrepresentation in gifted education, dual exceptionalities, creating culturally responsive classrooms, and increasing family involvement. Dr. Frazier Trotman Scott has conducted professional development workshops for urban school districts and has been invited to community dialogs with regard to educational practices and reform. She has written and coauthored several articles, has made numerous presentations at professional conferences, and has coedited six books. She is also on the editorial board for multiple journals and has served in leadership roles in professional organizations.

James L. Moore III, Ph.D., is the vice provost for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer at The Ohio State University, and serves as the first executive director of the Todd Anthony Bell National Resource Center on the African American Male. He is also the inaugural Education and Human Ecology Distinguished Professor of Urban Education in the College of Education and Human Ecology. Dr. Moore is internationally recognized for his work on African American males. He has published more than 140 publications; obtained more than $25 million in grants, contracts, and gifts; and given more than 200 scholarly presentations and lectures throughout the United States and other parts of the world. In both 2018 and 2019, Education Week named him as one of the 200 most influential scholars and researchers in the United States who inform educational policy, practice, and reform.