In this age of the pandemic that has shut down our businesses, our economy, and our lives, it is timely to consider another critical issue that has impacted the health of our educational institutions. It is the issue of the lack of provision of differentiated curriculum for our top learners. I am referring to our gifted and high-aptitude learners who sit through repetition, misinformation, and tedium in the name of education in core areas of learning. Although some may have access to high-quality gifted programs, the majority of these students do not. In many states, teachers receive no preparation to work with these learners through certification or endorsement, students do not have guarantees of acceleration best practices due to lack of state policies (see National Association for Gifted Children & Council of State Directors of Programs for the Gifted, 2015), and curriculum standards have been used as a cudgel to define learning both downward and in a uniform sameness for all learners, despite students’ abilities to perform at higher levels (VanTassel-Baska, 2019).

What are the curriculum differentiation features that must be enacted to prevent the continuation of this situation? I propose 10 differentiation methods that can alleviate the conditions in schools and classrooms that limit these top learners, some of whom may go on to find the solutions to pandemics such as ours today, in the form of vaccines, medicines for treatment, and social infrastructure that can protect our institutions.

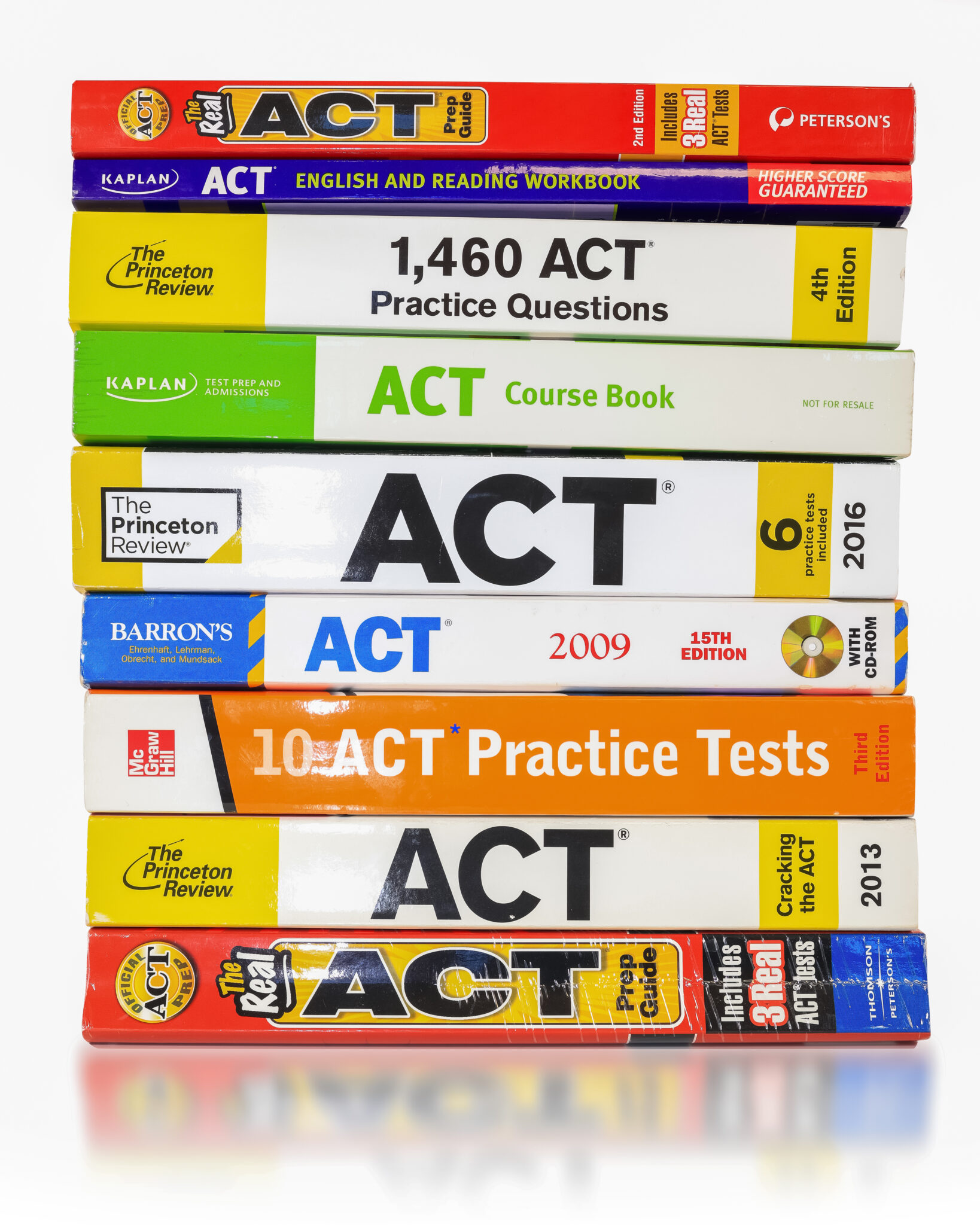

1. Apply diagnostic testing in all core subjects (i.e., reading, writing, math, science, and history) at the beginning of each year to determine readiness levels for advanced instruction before finalizing curriculum. Always assume some students will exceed expectations for content-specific knowledge and higher order thinking processes that can be applied in the service of difficult problems. For example, we have known for more than three decades that some students can acquire perfect scores on the math section of the SAT without ever taking algebra or geometry even though problem types related to these topics are on the test.

2. Group three to four students into instructional pods based on the results of the testing in each subject area. The size of groups matter for gifted students in respect to “air time,” but the groups also require sufficient diversity in thought to handle challenging work. When possible, even smaller groups of two are ideal for some collaborative work. Most grouping studies support grouping gifted students together for purposes of providing advanced instruction (Rogers, 2015; Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2016). When diagnostic assessment is used liberally, additional students may become part of a gifted pod based on readiness. Assessment and entry to the program by subject is a critical component of using assessment data, as opposed to requiring requisite high score levels in all subject areas for entry. Thus, verbally gifted students may participate in the language arts portion of advanced instruction if they are testing two grade levels beyond placement even though they may not perform at the same level in math or science.

3. Match instructional material to the level of each pod. For example, in reading, Lexile levels should dictate choice of reading material along with other criteria such as topics and issues to ensure that the material is advanced enough for the group. Reading level should drive vocabulary development, writing assignments, and other linguistic endeavors. In math, placement in learning groups should be done after a comprehensive math diagnostic that assesses understanding of mathematical topics to be studied during the year (end-of-year assessment), not just by the pacing guide for the fall. A test of scientific understanding of the research process (such as Fowler’s [1990] Diet Cola Test) should serve as the preassessment in science, as it will provide a clear sense of student capacity to reason scientifically through designing an experiment. Doing well on such a measure suggests readiness to engage in science at a deeper and fuller level than the core curriculum provides.

The results of these assessments should lead to the use of advanced materials in the classroom. The field has available research-based tools in all subject areas for working with gifted students. These should be the new core for gifted learners. Designed to accommodate developmental differences as well as intellectual ones, these materials can offer needed challenge in the basic subject areas. Materials include already differentiated reading material, writing assignments, and project assignments, all calibrated to work with gifted learners at different stages of development (see VanTassel-Baska & Baska, 2019).

4. Teach each group at the conceptual level able to be mastered. Grouping learners by their capacity to handle abstraction makes more advanced instruction possible. One strength of gifted learners is their ability to handle abstraction and to engage with challenging problems. In history, for example, many gifted learners can best understand specific events by contextualizing them in a period of time, such as an era or across a decade, within a major historical idea like systems or models, and by studying data on stakeholders and evidence on their perspectives. Using this as a model of organization, students can study relevant people in relationship to events across time, culture, and geography. For example, treating economics as a set of systems that have elements, boundaries, inputs, interactions, and outputs allows students to analyze similarities and differences of a free market system versus an oligarchical model. Comparing the perspectives of stakeholders allows students to understand how stakeholders may have different assumptions and beliefs, and make different inferences about the same set of data and evidence. Using such an approach to teach history requires inquiry-based instruction that is challenging, encouraging openness, and promoting critical thinking and problem solving. Students who show advanced ability to solve problems, handle thinking skills with ease, and elaborate processes for their work are ready for greater challenge as well.

5. Teach each group through a combination of reading, writing, and inquiry-based project models. These strategies should be applied daily through different technologies as feasible. For example, have students read two Lexile-level-appropriate articles online. After reading, ask students to compose a story about a character called Pandemic who provides his life story and insight into the how and why of his behavior. Allow students 15 minutes to create their stories. (They probably will not finish.) Have students share their stories in their pods. In the whole group, ask students to respond to the following questions:

- What have you learned through your peers’ stories about Pandemic (and the pandemic)?

- What evidence suggests that the pandemic will continue to spread, based on the data you have interpreted?

- What are the implications if the pandemic does continue unabated . . . for businesses . . . for schools . . . for the election?

Responses may be provided from each pod after discussion and shared with the total group. Then, as a whole group, create a web about the pandemic. Each student can then label the web and write an ending to the story.

6. Assess high-end learning through multiple approaches. In the case of studying the pandemic, students should be assessed on their writing acumen and interpretation of the articles they read through the developed story and through the responses they provided for the story ending. A standard rubric may be applied or a tailored one constructed. Group work in the pods may also be assessed on the criteria of collaboration, creativity, problem solving, and initiative. A strong combination of performance-based models, such as writing combined with group process skill markers, provides effective ways to assess important growth of gifted students’ goals and outcomes.

7. Encourage the use of metacognitive and self-assessment approaches with gifted learners. Ask students to react to the nature of learning they have experienced and the instructional processes that were used to facilitate that learning, and to reflect on the changes that have occurred as a result of daily learning in school. Self-assessment that asks students to identify the areas of learning in which they feel they have made progress and the areas in which they need more assistance to grow can also be useful forms of assessment.

8. Plan for the long term with gifted learners. What does their academic plan look like across the years they are in school? Has this plan been discussed with students and their parents? Because these students are capable of finishing the K–12 sequence a few years early, there is a need to map out their areas of academic strength in a deliberate way. Plans also need to be made early for extracurricular opportunities, including competitions. These ideas, along with suggestions about how to access such opportunities, should also be shared with parents. Create a scope and sequence chart for each subject area and for elective opportunities available for gifted learners at each stage of development.

9. Provide college and career information to students and parents as early as fifth grade. Students need to know what their options might be with regard to colleges and programs based on their interests and abilities. Concern for scholarship assistance needs to begin at this level as well. What might be affordable for students and families, based on income barriers? What colleges are best for students who want to become doctors or teachers? What do families look for in that regard?

10. Include a career preparation component at all levels, includingwithin a counseling program for the gifted at the elementary level, within target classes at the middle school level, and as an elective option at the high school level. Doing so could provide the continuity necessary for students to see where their education is headed and why. Helping students create meaning and direction for the future is paramount to their school experience.

These are my top 10 guidelines for tackling the critical issue of differentiation of curriculum for gifted students in the classroom. We need to revise our efforts in schools to ensure that these codes are adopted and worked on, regardless of the nature and extent of existing gifted programs. Levels of curriculum differentiation are necessary at school and district levels as well as in the classroom (see Figure 1).

Just as testing controls the extent to which we can control a pandemic, so too we need testing and assessment to know, understand, and control our efforts to differentiate curriculum. Just as a plan is necessary to progress on making positive change in a pandemic, it is also necessary to bring about more positive outcomes in high-end learning. Just as individual differences provide the data necessary to treat patients for COVID-19, attending to student differences provides an important avenue for curriculum intervention that is responsive to need. We need an appropriate dosage of curriculum differentiation for a raging pandemic of educational neglect of our best learners. Follow the guidelines!

References

Fowler, M. (1990). The diet cola test. Science Scope, 13(4), 32–34.

National Association for Gifted Children & Council of State Directors of Programs for the Gifted. (2015). 2014–2015 state of the states in gifted education: Policy and practice data. http://www.nagc.org/sites/default/files/key%20reports/2014-2015%20State%20of%20the%20States%20%28final%29.pdf

Rogers, K. (2007) Lessons learned about educating the gifted and talented: A synthesis of the research on educational practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4),382–396.

Steenbergen-Hu, S., Makel, M. C., & Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (2016). What one hundred years of research says about the effects of ability grouping and acceleration on K–12 students’ academic achievement: Findings of two second-order meta-analyses. Review of Educational Research, 86(4),849–899. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316675417

VanTassel-Baska, J. (2019). Introduction to the special issue on evaluation. Gifted Child Today, 42(4), 2–4.

VanTassel-Baska, J., & Baska, A. (2019). Curriculum planning and instructional design for gifted learners (3rd ed.). Prufrock Press.

Joyce VanTassel-Baska, Ed.D., is the Jody and Layton Smith Professor Emerita of Education at William & Mary in Virginia, where she developed a graduate program and a research and development center in gifted education. Formerly, she initiated and directed the Center for Talent Development at Northwestern University. She has also served as the state director of gifted programs for Illinois, as a regional director of a gifted service center in the Chicago area, as coordinator of gifted programs for the Toledo, OH, public school system, and as a teacher of gifted high school students in English and Latin. Dr. VanTassel-Baska has published widely, including 30 books and more than 650 refereed journal articles, book chapters, and scholarly reports. She has received national and international awards for her work from the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), Phi Beta Kappa, World Council for Gifted and Talented Children, the American Educational Research Association (AERA), and Mensa. Her major research interests are on the talent development process and effective curricular interventions for the gifted.