Underachievement is an important topic when it comes to the education of gifted students. The lack of high-level performances is seen as a missed opportunity in personal development and a missed result of education. This article defines and discusses the definition of underachievement, explains the concept of learning, and addresses ways that executive functions and skills influence the learning process.

Examining Potential and Performance

Performance in school alone is not reliable when it comes to recognizing gifted potential. Not every gifted student performs at a high level or demonstrates the characteristics of a high achiever. The same is true for high-achieving students because not every high achiever is a gifted student. Therefore, high academic achievement should be seen as only one of many indicators that a student might be gifted. If a student is achieving at a low level and, at the same time, other indicators of giftedness are being observed (e.g., an IQ > 130), the low achievement should not be the only consideration when decisions are made regarding whether or not the student would benefit from gifted services.

However, this article is not intended to discuss how gifted potential should be recognized. It is intended to argue that even without a formal label of being gifted, education should be challenging for all students, including bright students who are not identified as gifted. Giftedness refers to a student’s developmental potential (Gagné, 2010; Heller, 2010; Sternberg, 2002; Subotnik, Olszewski-Kubilus, & Worrel, 2011). This potential can be expressed in different domains, mentally or physically. In this article I focus on students who have the potential of intellectual giftedness. Students who have the potential to be intellectually gifted will, under the right circumstances, develop this potential in a way that enables them to excel in one or more academic domains, learn at a rapid pace, and be able to demonstrate their potential through achievement in school. (Subotnik et al., 2011). There is reciprocity between the developmental process, the student’s ecological system, and the student’s personality. The interaction between these different factors influences the developmental process and the propensity of the student to excel (Gagné, 2010; Freeman, 2010, 2013; Reis & McCoach, 2000; Subotnik et al., 2011; Van Gerven, 2013a; Van Meersbergen & De Vries, 2013). According to Gagné (2010), a talented student demonstrates the ability to master systematically developed competencies in at least one field of human activity to a degree that places the individual among the top 10% of “learning peers.” The word achievement relates directly to the evidence of mastery of these systematically developed competencies (Sternberg & Zhang, 1995). But is it correct to state that if a gifted student does not demonstrate his potential by performing at high levels in school that the student is an underachiever? That question is a challenge on its own merits when it comes to education and the role of the teacher, but I will address that later in this article.

Underachievement often is seen as the discrepancy between a student’s achievement and a student’s potential. Mooij, Hoogeveen, Driessen, van Hell, and Verhoeven (2007) suggested that this discrepancy should be considered as an indicator of underachievement when the student’s achievement is at least one standard deviation below his score on an intelligence test. According to this definition, twice-exceptional students should be considered underachievers because their achievements in the domain(s) of their disability are often one or more standard deviations below what might be expected based on their intelligence (American Psychiatric Association, 2014; Brody & Mills, 1997; Kroesbergen, 2017; van Gerven, 2017; Weterings, 2017).

Considering the fact that gifted students who have been identified with a learning disability or a behavioral disorder are often still able to perform at an above-average level, one can surmise that, within the domain of the disability and the domains affected by the disability, they are often able to compensate by performing at such a high level that the difficulties they experience due to the (learning) disability are almost invisible. In addition, we know that twice-exceptional learners are often willing to put forth huge efforts to achieve at this relatively high level (Weterings, 2017). So, underachievement is about more than just the discrepancy between intellectual potential and achievements (Webb et al., 2005). Therefore, twice-exceptional students should not be considered underachievers in the domains that are affected by their disability (Reis & McCoach, 2000).

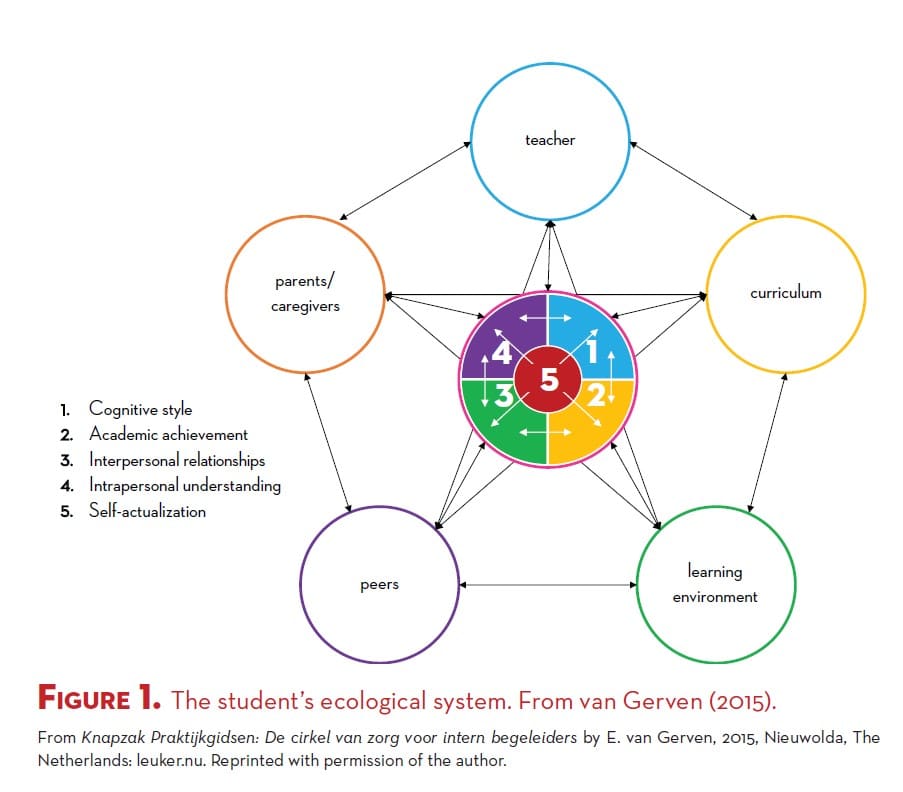

Sousa (2003) explained that underachievement is circumstantial, meaning that a student can perform below his potential at school, but might excel outside of school or at school in another context with a different teacher, in another subject, or even with different peers. The concept of the influence of the student’s ecological system (Van Gerven, 2015; Van Meersbergen & Jeninga, 2012) on his performance and well-being puts this in an even broader perspective. It implies that the fluidity of the profiles of Betts and Neihart (1988, 2010) is even more influential when they are interpreted in the context of day-to-day practice at schools.

In Figure 1, the influence of the student’s ecological system on his performance and well-being is visually represented. As in many conceptual representations of Response to Intervention (RtI), the student is placed in the center of action (Pameijer & Van Beukering, 2007; Robertson & Pfeiffer, 2016; Van Meersbergen & De Vries, 2013). Cognitive style, academic achievement, interpersonal relationships, and intrapersonal understanding influence the student’s self-actualization. These five factors interact with each other. Each factor is influenced by five external factors: the teacher, the parents/caregivers, the curriculum, the physical learning environment, and peers. At the same time, all of these factors are influencing each other as well. This model not only shows the complexity of a (gifted) student’s personal development, it also shows the complexity of educating the student, and, in turn, the complexity of the concept of underachievement.

Bearing all of this in mind, the following definition of underachievement takes shape:

Underachievement means for a longer period of time performing and achieving at a significant lower level than what might be expected based on the student’s intellectual potential under optimal educational circumstances, and without being hindered by a specific learning disability or behavioral disorder.

(Van Gerven, 2013a, p. 16)

At this point I’ll go back to where it all starts, the core business of education: learning.

When Teaching Results in Learning

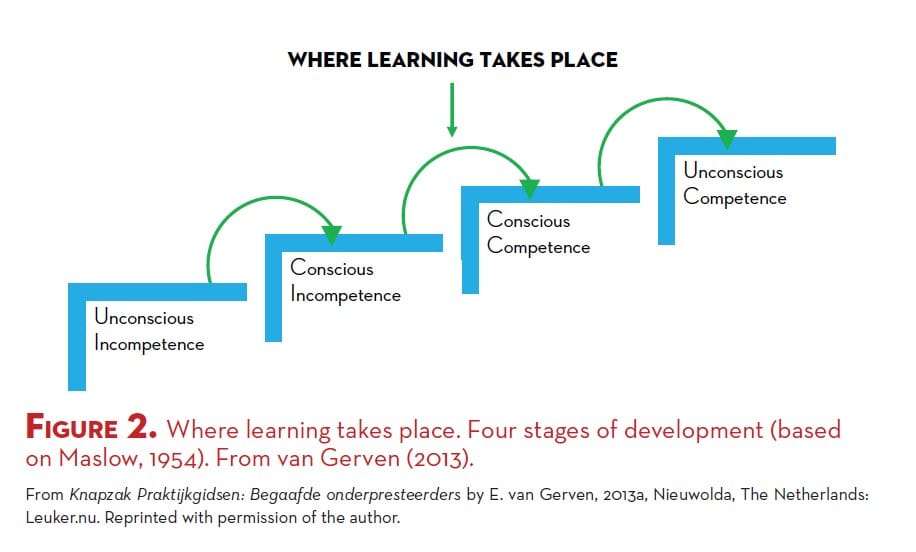

Learning isn’t just something that mysteriously happens for students. A good education is characterized by the teacher intervening purposefully in a way that makes it possible for a student to develop his potential by working hard and exerting effort in a well-prepared educational environment (Claxton & Meadows, 2009; Hattie, 2013; Marzano, 2007). In this context, the student goes through four stages of development (Maslow, 1954):

- Unconcious incompetence: One is unaware that there are competences to develop.

- Consious incompetence: One is aware that there are competences to develop and feels the need to develop the competencies.

- Consious competence: One has mastered new knowledge and/or skills and is aware of the newly mastered competences.

- Unconsious competence: One has internalized the acquired knowledge and skills and is able to put them to use at an automatized level.

Learning takes place in the period of transition between conscious incompetence and conscious competence (Maslow, 1954; see Figure 2). The application of newly acquired knowledge and skills in the following stage (between conscious competence and unconscious competence) is to be seen as practicing in the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978). In both stages, the teacher willfully intervenes in a way that changes the student’s knowledge, skills, and behaviors. A student who is learning will make mistakes, ask questions, and experience uncertainty. The teacher accepts that, when the student starts working on the assignment, he is not yet competent. In order to help the student in this process of mastery and becoming competent, the teacher instructs the student, supports him, and offers him the following on a daily basis: Vitamin T for Trying, Vitamin F for coping with Failure, Vitamin D for coping with Disappointment, Vitamin P for Perseverance, and Vitamin C for Celebrating successes. (Van Gerven, 2013b)

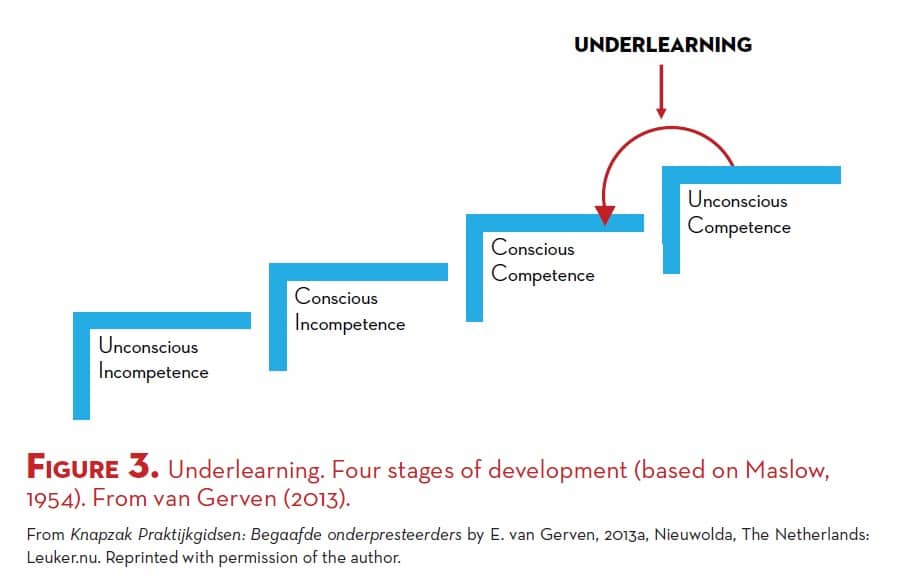

Without realization or intention on the part of the teacher, gifted students often are offered classroom assignments that match the ability of most students in the classroom, but that are below the personal learning potential of bright students. In their experience, school may have become the place where they are asked to complete assignments that involve new content but, they are still able to easily master the new knowledge and skills (moving from consciously competent to consciously competent) (see Figure 3) while most students in a classroom have a true learning experience as they complete their assignments (moving from conscious incompetent and to conscious competent). Having explained this and taking in consideration that learning is education’s core business, I propose that we, as educators, should not be focused on the idea that some gifted students are underachievers, but instead on the idea that most gifted students are underlearners.

It is important to realize that the student’s experiences in this learning process are shared with every child in the educational environment (Claxton & Meadows, 2009). Teachers typically build their expectations on a student’s prior achievements and performances in the classroom. As a result, the teacher may expect a gifted student to complete a new assignment with 100% mastery and without any help. The same applies for parents and—just as important—for peers. Everyone expects that the gifted student will excel time after time. Educators need to keep in mind that if a student is able to complete an assignment demonstrating 100% mastery without putting forth any effort, the student is most likely not being challenged at a level commensurate with his personal learning potential. In fact, when a student is truly learning, it is not likely that he will be able to demonstrate 100% mastery without any instruction or support. The greatest risk in this situation is not that the student may develop a so-called fixed mindset; instead, the real risk may be that when the student faces challenges, the environment stops supporting him as soon as his performance results are not in line with expectations of those teaching him. When the gifted student is truly learning and trying to move from conscious incompetence toward conscious competence, the teacher may tend to withdraw support and offer the student a less challenging activity so that he won’t make mistakes and is able to complete his assignments independently. If this happens several times consecutively, the student is not encouraged to stay with an activity and truly learn; instead, the activity is replaced with a learning experience on a lower level. In this situation, the educational environment unconsciously supports behavior that leads to underlearning.

Executive Skills

While learning, students develop their executive functions (Cooper-Kahn & Foster, 2014). Gifted students are no exception. Executive functions are cognitive processes that are required to control one’s behavior in order to be able to finish a task adequately within the time that has been given and in a way that the required standard is met (Cooper-Kahn & Foster, 2014; Dawson & Guare, 2009; Kroesbergen, Verkaik, & van Gerven, 2017). Executive functions can be described at two levels: a cognitive level and a behavioral level. The cognitive level refers to the processes that control thinking as well as behavior. There are three important executive functions: inhibition, shifting, and updating (Cooper-Kahn & Foster, 2014; Dawson & Guare, 2009; Kroesbergen et al 2017). Inhibition is the ability to suppress dominant reactions and, therefore, sustain attention, remain quiet when sensible, and the like. Shifting refers to the ability to switch attention from one thing to another and to switch between required behaviors. Updating is the ability to store new knowledge and skills and connect new information to earlier acquired information. The combination of shifting and updating results in the ability to be flexible. Executive functions are mental processes, but what goes on in your head can be made visible in your actions. The behavioral levels of executive functions are the executive skills. Based on the triad of inhibition, shifting, and updating, these skills can be divided in three groups. The individual skills belong together as horse and carriage and they continually influence each other.

- Inhibition

- Response inhibition

- Emotional control

- Sustained attention

- Shifting

- Flexibility

- Task initiation

- Updating

- Metacognition

- Working memory

Based on the abovementioned skills, Dawson and Guare (2009) distinguished a fourth relevant group of skills that can be seen separately:

- Planning

- Planning and prioritization

- Organization

- Time management

- Goal directed persistence

The way these executive skills develop depends partially on predisposition and partially on the educational context in which the student learns. It’s a bit of a chicken and egg situation. One needs executive functions in order to be able to learn, but one has to be placed in a situation where learning is required in order to transform these functions into skills.

According to Gathercole and Alloway (2013), executive functions are a reliable predictor for school success. This is quite logical considering that the way we teach often calls for more of a student’s executive skills than of his intelligence. Research from Kornmann, Zettler, Kammerer, Gerjets, and Trautwein (2015) showed that students with good executive skills are more likely to be recognized as being gifted than students without those skills, even if they are not gifted but have an IQ just above average and their school performances/successes are based on their well-developed executive skills. Despite their high IQs, gifted students with effective executive functions who are not being challenged to use them in an educational context are less likely to be recognized as gifted (Kornmann, Zettler, Kammerer, Gerjets, & Trautwein, 2015; Kroesbergen et al, 2017).

So, learning in itself is a state of mind that is needed during childhood to provide a person with the opportunity to develop the skills needed to become a successful, intelligent adult (Dweck, 2006). The call for executive skills becomes more intense under the following circumstances:

- The less familiar the task, the more you’ll experience the task as difficult. The more difficult a task, the bigger the call to apply executive skills.

- The complexity of the mental procedures that are required for a task increases with the number of steps that are required for the task and the lack of familiarity with the individual steps included in the task. Increasing complexity means increasing the use of executive skills.

- Learning becomes more difficult if the gap between old and new competencies increases. The bigger the gap, the more executive skills are required.

- If a task requires the combination of several mental procedures (i.e., in enriching tasks) the complexity of the task raises to a superlative level. The more steps you have to take, the more combinations you have to make, and the less familiar you are with them, the more you need to effectuate your executive skills. Therefore, higher order thinking skills, as described by Marzano and Kendall (2007), call for more executive skills than tasks at the levels of recognizing, recalling, and executing.

Based on research, we might assume that gifted students have good executive functions as long as they are not hindered by a specific learning or behavioral disability (Kroesbergen et al., 2017). If a gifted student is educationally challenged, the student will be able to put these well-developed executive functions to use and transform them to well-used executive skills. But in day-to-day practice we might observe that not every gifted child has well-developed executive skills. That raises the question about the origin of the problem. If there is no neuro-biological explanation for the less developed skills, the answer should be sought in the student’s educational context. The development of executive functions on the cognitive level as well on the behavioral level is being hindered under the following circumstances:

- From an early age, the gifted student is placed in an educational context wherein he was mostly familiar with the mental procedures that are required.

- The gap between formerly developed competencies and the opportunity to acquire new competencies is too small to create true learning experiences.

- Only lower order thinking skills have been taught and no complex mental procedures have been required.

- The student is allowed to withdraw from learning experiences because he doesn’t consider them to be “fun” experiences.

As a result of these circumstances, good functions won’t transfer to good skills. This is where the domino effect comes in: Without mastered skills, achievement stays behind; without achievement, no enrichment activities are offered; without enrichment activities, the chance that a gifted student might develop effective executive skills decreases rapidly.

This domino effect describes an educational situation in which underlearning and underperforming is (unconsciously) encouraged. It is likely that underachievers and underlearners have not developed the necessary executive skills. At this new challenging level, the student is confronted with an assignment that makes him consciously incompetent. This student has not experienced this before and is now forced to take on the challenge by himself (“You are such a good student, you can do this on your own.” or “I’m sorry, I have to invest my time in the students who need more help.”). Under these circumstances, it is only normal that the student experiences a frightening situation. It is not likely that he takes on the challenge with which he is confronted. The emotions he has to deal with are those of being afraid of the unknown and the fear of failing (Whitley, 2001). The behavioral model of Marzano and Kendall (2007; can be viewed as p. 16 of http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/172608.pdf) depicts how this process works.

Once a task is offered, the self-system is activated (Marzano & Kendall, 2007). The self-system can be seen as the part of one mind where real decision making takes place. Based on schemata in this system the student will determine whether or not he is motivated for a task (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). Basically, this is where Deci and Ryan’s (2000) triad of relationship, competence, and autonomy comes in. Questions in a student’s mind that are steering the decision making process can be: Do I relate positively to the learning objectives of this task? Am I competent enough to take this task on?” and “Am I in a position that offers just enough autonomy to make my own choices during the learning process?”

In their article ‘Executieve functies en begaafdheid’ Kroesbergen, Verkaik en Van Gerven (2017) explain how the process described in Marzano and Kendall’s behavioral model will take place in day-to-day practice. The following is based on this article. In the exploration of the task at a metacognitive level, the student estimates his chances for success. According to Marzano and Kendall (2007) he does this by checking at a cognitive level to determine if knowledge and skills are developed enough to have a chance to be successful. If he concludes that it is not likely that he will be able to end the task as successfully as everyone expects him to, motivation to become engaged in the task will drop significantly. This influences the executive function of task initiation because as a result of the lack of motivation, he drags his feet and does not initiate working on the assignment. Once started, he is not able to sustain his attention as fear of failure distracts him (De Bruin-De Boer & Van Gerven, 2009). It might even be that due to the fact that basic skills for the task are not yet acquired, and he has to shift his attention to seemingly unrelated, simple activities to acquire those skills (Marzano & Kendall, 2007). By doing so, the gifted student might endanger his social status of being the one who is always successful (Weterings, 2017). At this point other students might see him as the one who boasts of knowledge but isn’t able to do simple things. The concern that this might happen adds to the level of anxiety that has already been raised by being confronted with the feeling of being conscious incompetent (Van Gerven, 2013a). If one takes into account that with group or cooperative learning assignments a gifted student hardly needs to plan and prioritize, it may be that time management skills are not developed effectively (Kroesbergen, et al, 2017). And if the tasks are really easy, the student has no need to organize his behavior to structure a task, so another executive skill won’t develop. Under the circumstances as described, the self-system has decided not to become engaged.

Being put into an educationally challenging situation can be a very frightening experience. After all, the student is not yet competent and therefore he is out of his comfort zone. Feelings of insecurity are natural in a moment like that (Vygotski, 1978). Coping with these feelings of insecurity takes practice in order to develop a good coping strategy (Van Gerven, 2013a, 2013b). This practice can only be offered if challenge is offered from the very first day at school. In that case the student might attempt to engage in the learning experience because that is the expectation and every other child is doing the same; however, if a student does not experience a true educational challenge during the first 1, 2, 3, 4, or even 5 years of his education, the chances of developing coping strategies to deal with feelings of anxiety and insecurity whilst being still incompetent might be lost (van Gerven, 2013a, 2013b). The student might head for the closest mental “emergency exit” and refrain from becoming involved in a task instead of attempting to engage in the assigned task. His escape may be to state that the assignments are boring or even that he is not bright enough for such a complex task, therefore deciding that the challenge is not worth taking on (Dweck, 2006). The student may be excused from this assignment, another challenge may be offered, and the entire process starts all over again.

If the above-mentioned scenario is repeated time and again, underlearning cannot be reversed or overcome simply by presenting the student with some enrichment tasks or participation in an enrichment project. A completely different attitude for all involved in the student’s learning environment is required (De Bruin-de Boer & van Gerven, 2009; Galbraith, Delisle, & Delisle, 2002).

A Different Perspective on Underachievement

A superior level of mastery requires intense practicing; after all, practice makes perfect. Failure and practicing go hand in hand. When a gifted student embarks on the acquisition of new content and/or skills, one cannot expect that a superior level of mastery will emerge on the spot (Matthews & Folsom, 2009). A gifted student who is still practicing to master a new competence and putting in effort to do so cannot be considered an underachiever if he is experiences failure during this process. One must consider that failing makes visible only what still has to be learned (Dweck, 2006). The assumption that a gifted student can be recognized by his constant high achievements does not acknowledge the natural characteristics of the learning process. Venderickx (2017) compared this process with the scouting and training of young athletes. When a young athlete is scouted, an intensive training program starts. Scout, trainer, and athlete accept that the innate gift still has to be developed. No one expects the young athlete to be as good as an Olympic medal winner who has had years and years of practice. All involved realize that climbing to the top in any field is a struggle that can only be overcome by putting forth a joint effort. So why expect anything else from the student with the innate ability for academic success?

The starting point should be within the educational context where the student is placed and offered learning opportunities to perform, learn, and achieve at a maximum level. If the student’s achievement does not match the teacher’s expectations because she has another perspective on the student’s abilities, it says more about the educational context and the teacher’s personal mental framework than about the student (Van der Wolf & Van Beukering, 2012). It says something about the balance between the results of the student’s effort and the degree to which the educational context has offered the necessary scaffolds for learning. The term underachievement therefore says more about the construction of the educational and developmental process than about the student’s ability or achievements. Turning this process implies that all partners in the student’s environmental system have to play a different role. The interaction between the factors in the environmental system should be forced into a new order (Van Gerven, 2013a, 2013b).

If a student’s behavior does not reflect his intelligence and learning potential, the student is sending out an SOS. Underachieving and underlearning are ways of behavior. Behavior is just the message. Behavior can change, but in order to accomplish change, an effort of all parties involved is necessary. The teacher wants the student to “do better.” Telling someone “to do better” does not lead to “improved achievement” if the educational environment doesn’t encourage to “feel better.” The same applies to the behavior of an underachieving or underlearning gifted student. If the teacher wants the student to change and begin to achieve, changing her own behavior is imperative. In order to make sure that the student can meet her expectations, the teacher has to adjust her pedagogical-didactical approach. By creating a learning environment in which an optimal balance exists among the offered educational level, the student’s capacities, the necessary scaffolding, and the student’s achievements, the chances for success are optimized (Galbraith et al., 2002; Hattie, 2013; Sternberg, 2009).

In day-to-day practice, there is a difference between what is maximally desirable and maximally workable. Often there is more desired than is workable. If this is the case, then the teacher should adjust her expectations. Under less optimal conditions it is unrealistic to expect that a student will be fully able to actualize his learning potential, because the teacher has not offered learning opportunities that address the needs of the student; however, it is unrealistic to expect that any educational setting can offer the maximum desired context for all students at all times. So, as always, the truth lies somewhere in the middle (Van Gerven, 2014).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2014). Handboek voor de classificatie van psychische stoornissen (DSM-5) Nederlandse vertaling van Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Amsterdam, The Nethlerands: Boom.

Betts, G., & Neihart, M. (1988). Profiles of the gifted and talented. Gifted Child Quarterly, 32, 248–253.

Betts, G., & Neihart, M. (2010). Revised profiles of the gifted and talented. Retrieved from http://talentstimuleren.nl/thema/stimulerend signaleren/publicatie/269-revised-profiles-of-the-gifted-and-talented

Brody, L., & Mills, C. (1997). Gifted children with learning disabilities: A review of issues. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30, 282–296.

Claxton, G., & Meadows, S. (2009). Brightening up: How children learn to be gifted. In T. Balchin, B. Hymer, & D. Matthews. The Routledge International Companion to Gifted Education (pp. 3–9). London, England: Routledge.

Cooper-Kahn, J., & Foster, M. (2014). Executieve functies versterken op school. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Hogrefe.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). De weg naar flow. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Boom.

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2009). Slim maar… Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Hoogrefe.

De Bruin-de Boer, A., & van Gerven, E. (2009). De sociaal-emotionele ontwikkeling van begaafde leerlingen. In E. van Gerven (Ed.), Handboek Hoogbegaafdheid (pp. 188–213). Assen, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Van Gorcum.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychology Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Ballantine.

Freeman, J. (2010). Gifted lives: What happens when gifted children grow up. New York, NY: Routledge.

Freeman, J. (2013). The long-term effects of families and educational provision on gifted children. Educational and Child Psychology, 30(2), 7–17.

Furman, B. (2006). Kids skills. Soest, The Netherlands: Nelissen.

Gagné, F. (2010). Building gifts into talents: Brief overview of the DMGT 2.0. Montreal, Québec, Canada: Université du Québec à Montréal.

Galbraith, J., Delisle, J., & Delisle, R. (2002). When gifted kids don’t have all the answers. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Gathercole, S., & Alloway, T. (2013). De invloed van het werkgeheugen op het leren. Handelingsgerichte adviezen voor het basisonderwijs. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: SWP.

Hattie, J. (2013). Leren zichtbaar maken. Vlissingen, The Netherlands: Bazalt Educatieve Uitgaven.

Heller, K. (2010). The Munich Model of Giftedness and Talent. In Heller, K.E. Munich Studies of Giftedness (pp. 3–13). Berlijn, Germany: Dr. W. Hopf.

Kornmann, J., Zettler, I., Kammerer, Y., Gerjets, P., & Trautwein, U. (2015). What characterizes children nominated as gifted by teachers? A closer consideration of working memory and intelligence. High Ability Studies, 26(1), 75–92.

Kroesbergen, E. (2017). Begaafde leerlingen met dyslexie. In E. van Gerven (Ed.), De Gids. Over begaafdheid in het basisonderwijs (2nd ed., pp. 243–253). Nieuwolda, The Netherlands: Leuker.nu.

Kroesbergen, E., Verkaik, D., & van Gerven, E. (2017). Executieve functies en begaafdheid. In E. van Gerven (Ed.), De Gids. Over begaafdheid in het basisonderwijs (pp. 225–242). Nieuwolda, The Netherlands: Leuker.nu.

Måhlberg, K., & Sjöblom, M. (2008). Oplossingsgericht onderwijzen. Antwerpen, Belgium: Garant.

Marzano, R. (2007). Wat werkt op school. Vlissingen, The Netherlands: Bazalt Educatieve Uitgaven.

Marzano, R., & Kendall, J. (2007). The new taxonomy of educational objectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

Matthews, D., & Folsom, C. (2009). Making connections: Cognition, emotion and a shifting paradigm. In T. Balchin, B. Hymer, & D. Matthews (Eds.), The Routledge international companion to gifted education (pp. 18–25). London, England: Routledge.

Mooij, T., Hoogeveen, L., Driessen, G., van Hell, J., & Verhoeven, L. (2007). Succescondities voor onderwijs aan hoogbegaafde leerlingen. Eindverslag van drie deelonderzoeken. Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Radboud Universiteit.

Pameijer, N., & Van Beukering, T. (2007). Handelingsgericht werken: een handreiking voor de intern begeleider. Leuven, Belgium: Acco.

Reis, S., & McCoach, B. (2000). The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly, 44, 152–170.

Robertson, S., & Pfeiffer, S. (2016). Development of a procedural guide to implement Response to Intervention (RtI) with high-ability learners. Roeper Review, 38, 9–23.

Sousa, D. A. (2003). How the gifted brain learns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Succescolle intelligentie. Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Sternberg, R. J. (2009). Teaching for successful intelligence: Principles, practices and outcomes. In J. C. Kaufman, E. L. Grigorenko, & , R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The essential Sternberg: Essays on intelligence, psychology, and education (pp. 183–194). New York, NY: Springer.

Sternberg, R. J., & Zhang, L. (1995). What do we mean by giftedness? A pentagonal implicit theory. Gifted Child Quarterly, 39, 88–95.

Subotnik, R., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(1), 3–54.

Van der Wolf, K., & Van Beukering, T. (2012). Gedragsproblemen in scholen. Het denken en handelen van leraren. Leuven, Belgium: Acco.

Van Gerven, E. (2013a). Knapzak Praktijkgidsen: Begaafde onderpresteerders. Nieuwolda, The Netherlands: Leuker.nu

Van Gerven, E. (2013b). Module 3, Teacher Education Course Specialist in Gifted Education. Almere, The Netherlands: Slim! Educatief

Van Gerven, E. (2014). Knapzak Praktijkgidsen. Uitdagend Onderwijs. Nieuwolda, The Netherlands: Leuker.nu.

Van Gerven, E. (2015). Knapzak Praktijkgidsen: De cirkel van zorg voor intern begeleiders. Nieuwolda, The Netherlands: leuker.nu.

Van Gerven, E. (2017). Begaafde leerlingen met ADHD. In E. van Gerven (Ed.), De Gids. Over begaafdheid in het basisonderwijs (2nd ed., pp. 279–296). Nieuwolda, The Netherlands: Leuker.nu.

Van Meersbergen, E., & De Vries, P. (2013). Handelingsgericht werken in passend onderwijs. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Perspectief uitgevers.

Van Meersbergen, E., & Jeninga, J. (2012). De ecologie van de leerling. Een systeemgericht model voor het onderwijs. Tijdschrift voor Orthopedagogiek, 51, 175–185.

Venderickx, K. (02/16/2017). Wat we kunnen leren van het coachen van topsporters. Keynote at the conference: Dé Dag over begaafdheid in het basisonderwijs. Groningen: Slim! Educatief.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Webb, J. T., Amend, E. R., Webb, N. E., Goerss, J., Beljan, P., & Olenchak, F. R. (2005). Misdiagnosis and dual diagnosis of gifted children and adults: ADHD, bipolar, OCD, Asperger’s, depression, and other disorders. Tucson, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Weterings, A. (2017). Begaafde leerlingen met ernstige reken- en wiskundeproblemen en dyscalculie. In E. van Gerven (Ed..), De Gids. Over begaafdheid in het basisonderwijs (2nd ed., pp. 255–278). Nieuwolda, The Netherlands: Leuker.nu.

Whitley, M. (2001). Bright minds, poor grades. New York, NY: Perigee Books.

Wolters, C. (2011). Oplossingsgericht aan het werk met kinderen en jongeren. gesprekken en werkvormen. Huizen, The Netherlands: Pica.

Dr. Eleonoor Van Gerven has studied pedagogy at Nijmegen University (The Netherlands). She is managing director of Slim! Educatief, a private teacher education institute at the postgraduate level. She educates teachers in gifted education with an emphasis on twice-exceptionality. She has published (in Dutch) more than 15 books on gifted education. She has more than 25 years of experience in teacher education and graduates from her programs are leaders in gifted education in The Netherlands.